Throwing Stones XII: Joltin’ News Flash

(This is Part XII. To read Part XI, click Throwing Stones XI: Out Of Time.)

In Part XI, the Stones ditched manager-producer Andrew Oldham and released a psychedelic album.

![]() In the wake of the disappointing Their Satanic Majesties Request, longtime scene watchers began dismissing The Rolling Stones as has-beens. With producer Andrew Loog Oldham out of the picture and their artistic stock at an all-time low, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards made two key decisions. The first was to forget about psychedelia and other pop trends and get back to being a rock ’n’ roll band. The second was to hire American Jimmy Miller as their producer.

In the wake of the disappointing Their Satanic Majesties Request, longtime scene watchers began dismissing The Rolling Stones as has-beens. With producer Andrew Loog Oldham out of the picture and their artistic stock at an all-time low, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards made two key decisions. The first was to forget about psychedelia and other pop trends and get back to being a rock ’n’ roll band. The second was to hire American Jimmy Miller as their producer.

Miller had produced two huge Brit R&B hits, “I’m A Man” and “Gimme Some Lovin’,” both of which featured a young Steve Winwood. Jimmy Miller knew his way around a studio. More importantly, his experience as a drummer meant he knew how to shape a groove and drive a song.

At the end of May, 1968, The Stones released “Jumpin’ Jack Flash.” A bracing blast of guitar-driven rock, “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” leapt to the top of the charts, bounding to number one in England and number three in the U.S.

At the end of May, 1968, The Stones released “Jumpin’ Jack Flash.” A bracing blast of guitar-driven rock, “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” leapt to the top of the charts, bounding to number one in England and number three in the U.S.

“Jumpin’ Jack Flash” was a slap upside the head of everyone who had written off The Rolling Stones–including rock critics, the mainstream press and the touchy-feely hippie culture. Musically, the Miller-produced single codified what would become the band’s signature sound, and defined the sound of rock ’n’ roll for more than a decade.

Lyrically, the song marked the beginning of a four-year period in which The Rolling Stones rode the Zeitgeist like no other act in the history of popular music. Far from a flower-power peace poem, “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” told the story of a battered survivor emerging triumphant–a street urchin reinvented as a star. As the sixties slid from halcyon to harrowing, the message was clear: Toughen up, or you’ll never make it in this world. It would prove to be timely advice. A year of unprecedented upheaval was less than half over.

In January 1968, the North Vietnamese laid siege to the American base at Khe Sanh. The battle would rage for more than five months. On January 23, North Korean forces seized the U.S.S. Pueblo. Days later, the North Vietnamese launched the Tet Offensive.

In March, a demonstration led by Martin Luther King, Jr. ended in a confrontation that left many injured and an African American teenager dead. The Johnson administration announced yet another troop increase in Vietnam, and war protestors at Columbia University were violently removed from campus buildings. On April 4, King was murdered in Memphis, sparking massive riots and National Guard deployments in major American cities.

In March, a demonstration led by Martin Luther King, Jr. ended in a confrontation that left many injured and an African American teenager dead. The Johnson administration announced yet another troop increase in Vietnam, and war protestors at Columbia University were violently removed from campus buildings. On April 4, King was murdered in Memphis, sparking massive riots and National Guard deployments in major American cities.

In May, student protests in France led to bloody battles with police. French unions joined the students in a massive general strike that pushed the country to the brink of revolution, and an angry President de Gaulle brought the military into play.

Shortly after midnight on June 5, Robert Kennedy was gunned down in the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. In August, the Soviets invaded Czechoslovakia, crushing the Prague Spring beneath the treads of their tanks. A week later, protests at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago led to a “police riot” as the Daley machine’s troops ran amuck.

That same month, the Stones released “Street Fighting Man.” A taut tribute to political confrontation, the controversial song was widely banned, and charted poorly. But in America, radio itself was undergoing a revolution. The rise of free-form FM was beginning to make the singles charts seem irrelevant, and heavy airplay on the new (non) format made “Street Fighting Man” an anthem.

Have you ever wondered why baby boomers take rock ’n’ roll so seriously? How the music went from being dismissed as teen fodder to being considered a formidable cultural force? Why so many people still give a rat’s rear-end about a bunch of rich old men who call themselves “The Rolling Stones”? The answer lies beyond “Satisfaction,” The Summer of Love, Some Girls and stadium shows. Because, when “Street Fighting Man” was released, it seemed less a song than a news flash from a source you could trust.

That was no small feat in 1968. Throughout the year, even the mainstream media’s belief in the establishment had been shaken to the core. At the end of February, Walter Cronkite broadcast an unprecedented report. The most trusted newsman in America declared that the U.S. Government’s version of events in Vietnam was a P.R. pipe dream. The nation was mired in a stalemate, and risking “a cosmic disaster.”

A few months later, a young CBS reporter named Dan Rather was roughed up by Mayor Daley’s goons on the floor of the Democratic convention. Knocked to the ground during a live broadcast, Rather struggled to reconcile the reality of his situation with his cherished beliefs about America. The rest of the world watched, and did the same.

In October, a peaceful protest march in Ireland was set upon by truncheon toting police, injuring over 100 and leading to two days of rioting in Derry. Mexican police and military troops opened fire on student protestors in Mexico City, leaving at least 45 dead and hundreds injured. Later that month in the same city, two U.S. athletes set off a scandal at the Olympic Games by giving the black power salute during a medal ceremony. In November, Richard Nixon won the presidency, narrowly defeating Hubert Humphrey.

In October, a peaceful protest march in Ireland was set upon by truncheon toting police, injuring over 100 and leading to two days of rioting in Derry. Mexican police and military troops opened fire on student protestors in Mexico City, leaving at least 45 dead and hundreds injured. Later that month in the same city, two U.S. athletes set off a scandal at the Olympic Games by giving the black power salute during a medal ceremony. In November, Richard Nixon won the presidency, narrowly defeating Hubert Humphrey.

In early December, the Stones released Beggars Banquet. Their seventh studio album, Banquet had been delayed due to a spat over its cover. The first version featured a graffiti-riddled public restroom. Sir Edward Lewis, President of Decca Records, was not amused. Potty-free artwork was eventually approved. The album was a huge critical and commercial success. Rolling Stone magazine declared it the “comeback of the year.”

At the height of the holiday season, astronauts aboard Apollo 8 orbited the moon. For the first time in history, human beings saw images of the earth as a whole planet. As one of the most turbulent years in modern history drew to a close, dread and disaster, riots and rock bands, wars and wishes for a better world were suddenly seen from an unprecedented perspective. Perhaps there was hope for us all after all.

At the height of the holiday season, astronauts aboard Apollo 8 orbited the moon. For the first time in history, human beings saw images of the earth as a whole planet. As one of the most turbulent years in modern history drew to a close, dread and disaster, riots and rock bands, wars and wishes for a better world were suddenly seen from an unprecedented perspective. Perhaps there was hope for us all after all.

(This concludes Part XII. Click now to read Throwing Stones XIII: The Devil And Mr. Jones!)

On June 1, 1967, the Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The iconic audio achievement of The Summer of Love, Pepper was the ultimate pop cultural game-changer. Brilliantly conceived, enthusiastically performed, technically innovative and wildly creative, the album was the product of extraordinarily high standards and a demanding schedule. Its arrival could not have been more perfectly timed.

On June 1, 1967, the Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The iconic audio achievement of The Summer of Love, Pepper was the ultimate pop cultural game-changer. Brilliantly conceived, enthusiastically performed, technically innovative and wildly creative, the album was the product of extraordinarily high standards and a demanding schedule. Its arrival could not have been more perfectly timed. Like Brian Jones, producer and co-manager Andrew Loog Oldham was struggling with mental health and addiction issues. Oldham’s talent for making money was exceeded only by his ability to spend it, and despite all of his success, he found himself in a constant financial pinch. Desperate for ready cash, Oldham slowly sold more and more of his stake in the Stones to co-manager Allen Klein.

Like Brian Jones, producer and co-manager Andrew Loog Oldham was struggling with mental health and addiction issues. Oldham’s talent for making money was exceeded only by his ability to spend it, and despite all of his success, he found himself in a constant financial pinch. Desperate for ready cash, Oldham slowly sold more and more of his stake in the Stones to co-manager Allen Klein. The Stones were contracted to Decca records through Oldham’s production company. Because that company would eventually own the masters, Oldham was responsible for all recording costs. During Oldham’s absences, Mick Jagger had become more involved in the band’s day-to-day operations. Jagger knew that studio time came out of Oldham’s pocket, and was well aware of Andrew’s iffy finances.

The Stones were contracted to Decca records through Oldham’s production company. Because that company would eventually own the masters, Oldham was responsible for all recording costs. During Oldham’s absences, Mick Jagger had become more involved in the band’s day-to-day operations. Jagger knew that studio time came out of Oldham’s pocket, and was well aware of Andrew’s iffy finances. Jagger and Richards snickered at Oldham’s motivational efforts, and often refused to acknowledge his presence at all. Progress was slow, painful and expensive. Mick Jagger seemed more interested in coming up with an elaborate graphics package for the new LP than recording it. Of course, the cost of the artwork would be coming out of Oldham’s cash flow.

Jagger and Richards snickered at Oldham’s motivational efforts, and often refused to acknowledge his presence at all. Progress was slow, painful and expensive. Mick Jagger seemed more interested in coming up with an elaborate graphics package for the new LP than recording it. Of course, the cost of the artwork would be coming out of Oldham’s cash flow. Mick Jagger and Keith Richards won their war with Oldham, but suffered heavy artistic casualties. The many months of chaotic sessions eventually birthed Their Satanic Majesties Request. Already dated when it hit the stores in December of 1967, the album was widely dismissed as a patchy Sgt. Pepper rip-off. The expensive 3-D lenticular cover only added to the absurdity. Dressed in cheesy medieval outfits and posed in front of a pint-sized plastic castle, the sheepish Stones appeared to be trapped in a photo booth at the world’s tackiest renaissance festival.

Mick Jagger and Keith Richards won their war with Oldham, but suffered heavy artistic casualties. The many months of chaotic sessions eventually birthed Their Satanic Majesties Request. Already dated when it hit the stores in December of 1967, the album was widely dismissed as a patchy Sgt. Pepper rip-off. The expensive 3-D lenticular cover only added to the absurdity. Dressed in cheesy medieval outfits and posed in front of a pint-sized plastic castle, the sheepish Stones appeared to be trapped in a photo booth at the world’s tackiest renaissance festival.

As word got around that the new generation of stars was experimenting with an array of illegal substances, a News of the World mole cozied up to the perpetually drug-dazed Brian Jones. When Jones prattled on about his favorite chemicals, his words turned up in the tabloid in no time. Demonstrating its usual high regard for getting the facts straight, the paper attributed Brian’s bleary-eyed blather to Mick Jagger. Jagger hired an attorney and filed a lawsuit against Britain’s top gossip rag.

As word got around that the new generation of stars was experimenting with an array of illegal substances, a News of the World mole cozied up to the perpetually drug-dazed Brian Jones. When Jones prattled on about his favorite chemicals, his words turned up in the tabloid in no time. Demonstrating its usual high regard for getting the facts straight, the paper attributed Brian’s bleary-eyed blather to Mick Jagger. Jagger hired an attorney and filed a lawsuit against Britain’s top gossip rag.

Jagger was arrested after admitting that four capsules found in a jacket pocket were his. Keith Richards had no drugs on him (Oh, the irony!) but was the owner of an ashtray that showed traces of marijuana resin. Robert Fraser was in possession of heroin and amphetamines. David Schneiderman, whose briefcase was likely full of drugs, told the police he was a photographer. He claimed the case contained exposed film that would be ruined if it were opened. The briefcase was not searched and he was not charged. Jagger and Richards smelled a set-up. Schneiderman, who traveled under a variety of aliases and held several false passports, slipped out of the country in short order.

Jagger was arrested after admitting that four capsules found in a jacket pocket were his. Keith Richards had no drugs on him (Oh, the irony!) but was the owner of an ashtray that showed traces of marijuana resin. Robert Fraser was in possession of heroin and amphetamines. David Schneiderman, whose briefcase was likely full of drugs, told the police he was a photographer. He claimed the case contained exposed film that would be ruined if it were opened. The briefcase was not searched and he was not charged. Jagger and Richards smelled a set-up. Schneiderman, who traveled under a variety of aliases and held several false passports, slipped out of the country in short order.

Andrew Loog Oldham insisting that the Rolling Stones behave themselves would have made a terrific Monty Python routine. Skipping the Palladium roundabout was exactly the kind of bad-boy publicity stunt he had routinely cooked up to feed the band’s anti-Beatles branding. But by 1967, Oldham was worried that the Stones were due for some serious backlash.

Andrew Loog Oldham insisting that the Rolling Stones behave themselves would have made a terrific Monty Python routine. Skipping the Palladium roundabout was exactly the kind of bad-boy publicity stunt he had routinely cooked up to feed the band’s anti-Beatles branding. But by 1967, Oldham was worried that the Stones were due for some serious backlash. Unfortunately, Andrew Loog Oldham had bigger problems. His depressions were growing longer, deeper and more frequent. Self-medicating with massive amounts of booze and drugs only made things worse. When Oldham sought professional help, he found himself at the mercy of a doctor whose ghastly overuse of electroshock therapy left the young manager in a fog even when he was sober. Adding to his woes, Oldham’s beloved Rolling Stones were turning on him.

Unfortunately, Andrew Loog Oldham had bigger problems. His depressions were growing longer, deeper and more frequent. Self-medicating with massive amounts of booze and drugs only made things worse. When Oldham sought professional help, he found himself at the mercy of a doctor whose ghastly overuse of electroshock therapy left the young manager in a fog even when he was sober. Adding to his woes, Oldham’s beloved Rolling Stones were turning on him.

Less than three years after starting out as a cover band playing local clubs, The Rolling Stones had morphed into an international phenomenon. They had racked an impressive string of hit singles and albums in Europe and America. Their concerts sold out quickly and ended in fans-gone-wild pandemonium. They were second only to The Beatles in the newly built Brit-rock pantheon, and Jagger and Richards were second only to Lennon and McCartney as chart-topping songwriters.

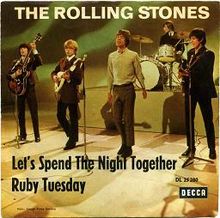

Less than three years after starting out as a cover band playing local clubs, The Rolling Stones had morphed into an international phenomenon. They had racked an impressive string of hit singles and albums in Europe and America. Their concerts sold out quickly and ended in fans-gone-wild pandemonium. They were second only to The Beatles in the newly built Brit-rock pantheon, and Jagger and Richards were second only to Lennon and McCartney as chart-topping songwriters. The band planned to kick off ’67 in style. They would headline The Ed Sullivan Show on Sunday, January 15, performing both sides of their new single for a gigantic primetime audience. Musically, “Let’s Spend the Night Together” and “Ruby Tuesday” were among the most radio-friendly tracks the Stones had ever recorded. The single would hit stores and radio stations the day before tens of millions of viewers caught the band on national TV. It couldn’t miss.

The band planned to kick off ’67 in style. They would headline The Ed Sullivan Show on Sunday, January 15, performing both sides of their new single for a gigantic primetime audience. Musically, “Let’s Spend the Night Together” and “Ruby Tuesday” were among the most radio-friendly tracks the Stones had ever recorded. The single would hit stores and radio stations the day before tens of millions of viewers caught the band on national TV. It couldn’t miss. Oldham must have loved that one. The Stones hair had been clean. Indeed, Brian Jones’ shimmering locks were enough to make a Breck® Girl jealous. The clothing issue seemed to center around Mick Jagger’s choice of a sweater instead of a suit or sport coat. Oldham agreed to dandy up his lead singer and let the show’s stylist wash his boys’ hair before the broadcast. Deal.

Oldham must have loved that one. The Stones hair had been clean. Indeed, Brian Jones’ shimmering locks were enough to make a Breck® Girl jealous. The clothing issue seemed to center around Mick Jagger’s choice of a sweater instead of a suit or sport coat. Oldham agreed to dandy up his lead singer and let the show’s stylist wash his boys’ hair before the broadcast. Deal.

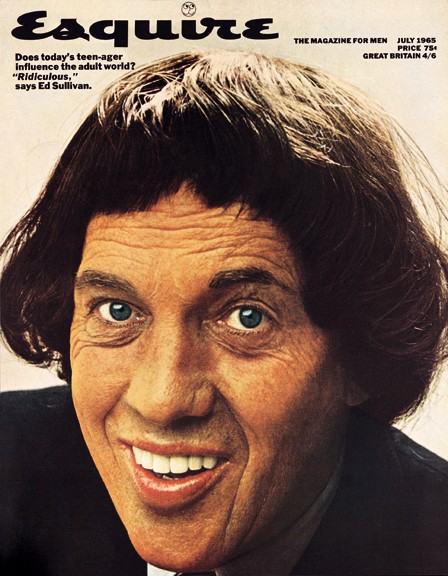

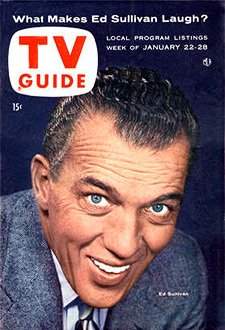

Ed Sullivan was the ultimate show business cipher. He couldn’t sing, dance, act or tell a joke. But he became one of the biggest stars, and the biggest star-maker, in television history.

Ed Sullivan was the ultimate show business cipher. He couldn’t sing, dance, act or tell a joke. But he became one of the biggest stars, and the biggest star-maker, in television history. Nobody ever accused Ed Sullivan of being telegenic. Devoid of the easy charm and relaxed demeanor television demanded, Sullivan came across as tense and intense. His smiles registered as grimaces. His eyes darted beneath his furrowed brow. He was stiff-necked and often listed to one side, and his lurching movements convinced some viewers that he suffered from palsy. Sullivan’s patter was stilted, his banter was boring and his awkward phrasing and strange pronunciations delighted amateur impressionists everywhere. His program was the closest thing to vaudeville on TV, and he always promised “a rilly big shew.”

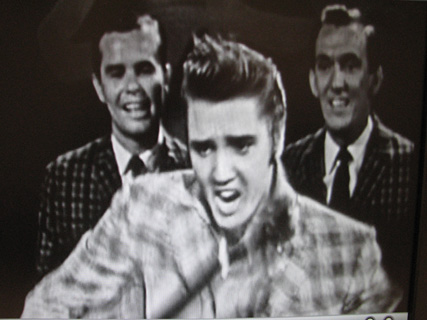

Nobody ever accused Ed Sullivan of being telegenic. Devoid of the easy charm and relaxed demeanor television demanded, Sullivan came across as tense and intense. His smiles registered as grimaces. His eyes darted beneath his furrowed brow. He was stiff-necked and often listed to one side, and his lurching movements convinced some viewers that he suffered from palsy. Sullivan’s patter was stilted, his banter was boring and his awkward phrasing and strange pronunciations delighted amateur impressionists everywhere. His program was the closest thing to vaudeville on TV, and he always promised “a rilly big shew.” Steve Allen’s show aired opposite Sullivan’s, and demolished Ed’s ratings the night that Elvis appeared. Sullivan did a world class flip-flop, booking Presley for three shows. The first drew 60 million viewers, a TV audience record. By the third show, Sullivan was praising Elvis on air as “a real decent, fine boy” while CBS cameramen framed the hillbilly hip-shaker strictly from the waist up.

Steve Allen’s show aired opposite Sullivan’s, and demolished Ed’s ratings the night that Elvis appeared. Sullivan did a world class flip-flop, booking Presley for three shows. The first drew 60 million viewers, a TV audience record. By the third show, Sullivan was praising Elvis on air as “a real decent, fine boy” while CBS cameramen framed the hillbilly hip-shaker strictly from the waist up. In January 1958, more than a year after Elvis’s final appearance, Sullivan ordered Buddy Holly not to play “Oh Boy.” Like Bo Diddley, Holly was appearing on the show to promote his current single, and was mystified by Sullivan’s last-minute meddling. Apparently, Sullivan had decided that the song was simply too energetic for his show’s audience. When Holly stood his ground, Sullivan cut his second song and ordered Holly’s electric guitar be turned down during “Oh Boy.” Holly rocked the house anyway. A flummoxed Sullivan later offered Holly more appearances. Avenging the slight to his Fender® Stratocaster®, Holly turned Sullivan down.

In January 1958, more than a year after Elvis’s final appearance, Sullivan ordered Buddy Holly not to play “Oh Boy.” Like Bo Diddley, Holly was appearing on the show to promote his current single, and was mystified by Sullivan’s last-minute meddling. Apparently, Sullivan had decided that the song was simply too energetic for his show’s audience. When Holly stood his ground, Sullivan cut his second song and ordered Holly’s electric guitar be turned down during “Oh Boy.” Holly rocked the house anyway. A flummoxed Sullivan later offered Holly more appearances. Avenging the slight to his Fender® Stratocaster®, Holly turned Sullivan down.

The Beatles chalked up six #1 U.S. hits in 1964. Their TV appearances shattered audience records, and their American tour was a runaway success. By the end of the year, English acts accounted for more than a third of all the singles to reach the American top ten. The British Invasion was rolling across the pop cultural landscape like a mechanized division. But the Rolling Stones were stuck in the trenches.

The Beatles chalked up six #1 U.S. hits in 1964. Their TV appearances shattered audience records, and their American tour was a runaway success. By the end of the year, English acts accounted for more than a third of all the singles to reach the American top ten. The British Invasion was rolling across the pop cultural landscape like a mechanized division. But the Rolling Stones were stuck in the trenches.

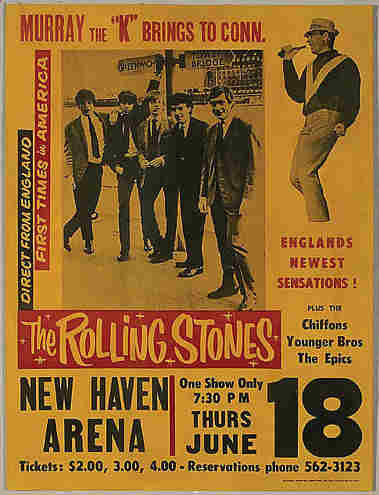

The Stones’ stateside fortunes changed dramatically when the band returned to America in the fall of 1964. “Time Is On My Side” was riding the rising tide of Brit hits into the top ten. Buoyed by a late October appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, the Stones began playing to full houses, and firmly established their anti-Beatles image in the U.S.

The Stones’ stateside fortunes changed dramatically when the band returned to America in the fall of 1964. “Time Is On My Side” was riding the rising tide of Brit hits into the top ten. Buoyed by a late October appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, the Stones began playing to full houses, and firmly established their anti-Beatles image in the U.S. The production team of Hugo & Luigi, who had worked on many of Cooke’s hits and owned an interest in some of his projects, turned down Klein’s buyout offers. The producers claimed that Klein responded by stonewalling them, making it impossible to learn what was going on with their stake in Cooke’s legacy. The duo eventually sold to Klein out of sheer frustration.

The production team of Hugo & Luigi, who had worked on many of Cooke’s hits and owned an interest in some of his projects, turned down Klein’s buyout offers. The producers claimed that Klein responded by stonewalling them, making it impossible to learn what was going on with their stake in Cooke’s legacy. The duo eventually sold to Klein out of sheer frustration.

depths of New York’s notorious Genovese mob family and crept into almost every aspect of the entertainment world. Roulette Records functioned as a record company while serving as a mob bank, scam, social club and money laundering operation. Men who challenged Morris Levy on business matters tended to suffer brutal beatings, get dangled out of windows or simply disappear.

depths of New York’s notorious Genovese mob family and crept into almost every aspect of the entertainment world. Roulette Records functioned as a record company while serving as a mob bank, scam, social club and money laundering operation. Men who challenged Morris Levy on business matters tended to suffer brutal beatings, get dangled out of windows or simply disappear. African-American owned record companies in the country.

African-American owned record companies in the country.