Throwing Stones VIII: Band Vs. Brand

(For Part VII, click Throwing Stones VII: Mr. Ed .)

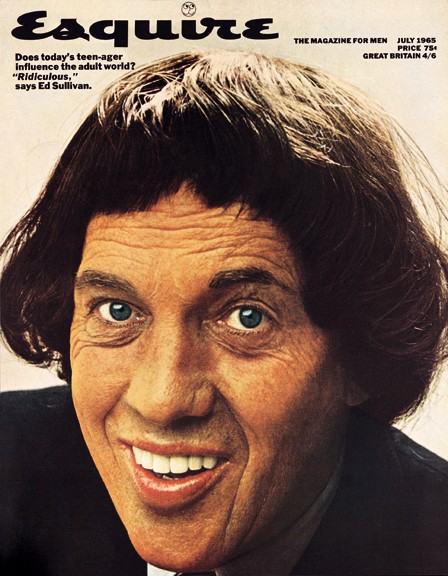

In Part VII, Ed Sullivan rose from the sports desk of an infamous tabloid to become the most popular impresario on primetime TV.

On Friday, January 13, 1967, Mick Jagger left London and flew to America to rendezvous with the rest of the Rolling Stones. Jagger dismissed press questions about travelling on such a dreaded day as silly superstition. His confidence appeared to be well founded.

Less than three years after starting out as a cover band playing local clubs, The Rolling Stones had morphed into an international phenomenon. They had racked an impressive string of hit singles and albums in Europe and America. Their concerts sold out quickly and ended in fans-gone-wild pandemonium. They were second only to The Beatles in the newly built Brit-rock pantheon, and Jagger and Richards were second only to Lennon and McCartney as chart-topping songwriters.

Less than three years after starting out as a cover band playing local clubs, The Rolling Stones had morphed into an international phenomenon. They had racked an impressive string of hit singles and albums in Europe and America. Their concerts sold out quickly and ended in fans-gone-wild pandemonium. They were second only to The Beatles in the newly built Brit-rock pantheon, and Jagger and Richards were second only to Lennon and McCartney as chart-topping songwriters.

Despite their success, the Stones were seen as dark, dirty and dangerous. They were outspoken, outrageous, uncompromising and unwilling to play showbiz games. Manager Andrew Loog Oldham’s anti-Beatles brand strategy had succeeded beyond anybody’s wildest dreams. The Beatles were great. But the Stones were badass. Even John Lennon envied their nasty image.

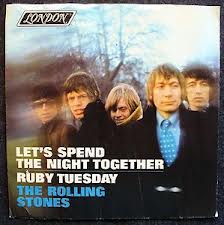

The band planned to kick off ’67 in style. They would headline The Ed Sullivan Show on Sunday, January 15, performing both sides of their new single for a gigantic primetime audience. Musically, “Let’s Spend the Night Together” and “Ruby Tuesday” were among the most radio-friendly tracks the Stones had ever recorded. The single would hit stores and radio stations the day before tens of millions of viewers caught the band on national TV. It couldn’t miss.

The band planned to kick off ’67 in style. They would headline The Ed Sullivan Show on Sunday, January 15, performing both sides of their new single for a gigantic primetime audience. Musically, “Let’s Spend the Night Together” and “Ruby Tuesday” were among the most radio-friendly tracks the Stones had ever recorded. The single would hit stores and radio stations the day before tens of millions of viewers caught the band on national TV. It couldn’t miss.

Mick Jagger’s Friday the 13th flight was uneventful. But his band’s luck was about to run out.

The Rolling Stone’s first Sullivan appearance in October, 1964, had provided a much-needed boost to their fall U.S. tour. Still, CBS had been deluged with calls and letters from irate viewers, who excoriated the Stones as unkempt, untalented, indecent and inappropriate for family viewing. Apparently a band that wore their hair longer than the Beatles but didn’t wear matching suits was too much for America to take—especially one that drove young female fans into a non-stop screaming frenzy.

Ed Sullivan vowed he would never book The Rolling Stones again. But the ratings had been high, and when Oldham inquired about a second appearance, Sullivan softened, responding that he would consider it if “…your young men reformed in the matter of dress and shampoo.”

Oldham must have loved that one. The Stones hair had been clean. Indeed, Brian Jones’ shimmering locks were enough to make a Breck® Girl jealous. The clothing issue seemed to center around Mick Jagger’s choice of a sweater instead of a suit or sport coat. Oldham agreed to dandy up his lead singer and let the show’s stylist wash his boys’ hair before the broadcast. Deal.

Oldham must have loved that one. The Stones hair had been clean. Indeed, Brian Jones’ shimmering locks were enough to make a Breck® Girl jealous. The clothing issue seemed to center around Mick Jagger’s choice of a sweater instead of a suit or sport coat. Oldham agreed to dandy up his lead singer and let the show’s stylist wash his boys’ hair before the broadcast. Deal.

Jagger donned a jacket when the Stones returned to The Ed Sullivan Show in May of 1965. They were back in February of 1966 as stars, performing their summer of ’65 smash, “Satisfaction,” and two more songs. Jagger, sans sport coat, had clearly mastered the art of playing to the camera, sending out one saucy stare after another to the folks at home. (Note to self: Try to work the word “saucy” into all future blogs.) The Stones made their fourth appearance on Sullivan the following September.

Clearly, the Rolling Stones and The Ed Sullivan Show had developed a mutually beneficial business relationship. Booking the band ensured high ratings, and high ratings drove ad sales and record sales alike. But before they hit the Sullivan stage that Sunday evening in early 1967, the Stones were informed that there was a problem.

Sullivan and CBS censors confronted the band and Oldham, explaining that the phrase “let’s spend the night together” was too risqué for American TV. After all, only married couples could spend the night together. (Wink, wink.) The Stones would have to make a teensy change to the lyric before show time. When the band seemed resistant, Sullivan became characteristically blunt: “Either the song goes, or you go.”

While anyone who examines the lyrics of “Let’s Spend The Night Together” can figure out where the singer is coming from, the wording is far from explicit. It doesn’t even contain the kind of smirk inducing double entendres found in 1950’s rock and R&B hits. But the very idea of the song scared the hell out of broadcasters.

Though the culture was changing rapidly, the sixties remained an era of heavy self-censorship in American broadcasting. The federal government strictly regulated the number of stations. There were no cable networks. A broadcast license was like a license to print money. Each of the big three TV networks owned a handful of flagship stations, and network execs lived in fear of an on-air slip-up that could cost them or their local affiliates their coveted licenses.

The Rolling Stones had a decision to make. And time was not on their side.

In his memoirs, Andrew Loog Oldham claims that a year or two earlier, the band would have walked. But now, everyone had a lot more to lose. Bill Wyman and Charlie Watts felt it was up to Jagger and Richards. Brian Jones was too zonked to care. Keith Richards, whose love of Lenny Bruce had familiarized him with American censorship, figured this was the way things worked. The ever-calculating Jagger rolled his eyes and quickly came up with “let’s spend some time together.” Deal.

Early in that night’s broadcast, the Stones delivered “Ruby Tuesday” to an enthusiastic audience. They reappeared near the end of the hour, and Mick sang “let’s spend some time together.” Jagger repeated his eye roll during the chorus, but his overall performance was so camped up that it was difficult to tell if the gesture was a comment on the revised lyric or simply part of the act.

The fallout was immediate. Like the Stones themselves, their fans had changed dramatically in a short time. Many were no longer screaming teenyboppers. In the wake of The Beatles and Bob Dylan, kids and critics were beginning to think of rock ’n’ roll as a legitimate art form. Musical preferences were worn as badges of honor. Bands were supposed to have integrity. And now, The Rolling Stones–the ultimate bad boys of British rock–had sold out to creepy old Ed Sullivan.

(This concludes Part VIII of Throwing Stones. Click now to read Part IX: Offstage Lines.)

George B.

Why do I feel entertained yet older when I read about these Brit Rockers mixing it up with Ed Sullivan? I was a pimply teen back then, but I can remember it so vividly! Great writing covering a fabulous time in music history, which is still going strong. The Stones should rename themselves “The Grateful Living!”

Eric B.

Thanks for reminding me of the many facts I had either forgotten or possibly never knew in the first place. I always loved the Stones. We used to buy their EPs from England back in ’68 because they weren’t available in the U.S. Keep up the good work!

Happ W.

Fascinating stuff. You make it seem like you were actually there. Were you? And how do I get an advance copy of Part IX?

Bryan T.

These posts always entertain me with interesting bits of info from stories that I’ve never heard in detail–only the vaguely generalized version of events. Good stuff, keep it coming.

Dan O.

Maybe those lyrics were just too saucy for Ed and the gang at CBS. I’m hugely enjoying this series. Can’t wait to find out what happens next (even though it’s already happened).

JoeVideo

Yeah, old Ed Sullivan was kind of creepy. I never could understand how that guy came to such prominence in broadcasting. Very interesting facts about the Stones. Learning so much about a band I always admired for sticking it out and not breaking up.

Chris L.

Nice read! I don’t know why, but the funny visual of Ed Sullivan struggling to make a high-tech “VOICE” judge’s chair spin around comes to mind. Shampoo would have been the least of his worries!