Throwing Stones XXI: Shattered

(This is Part XXI. Click here to read Throwing Stones Part XX: A Shot Away)

In part XX, the Stones struggled through their set at the violent Altamont free concert.

The Rolling Stones triumphant American tour had ended in tragedy. The badly shaken band members flew back to England the day after the Altamont free concert, leaving Road Manager Sam Cutler behind to deal with the fallout.

The Rolling Stones triumphant American tour had ended in tragedy. The badly shaken band members flew back to England the day after the Altamont free concert, leaving Road Manager Sam Cutler behind to deal with the fallout.

Though the Stones had promised to “take care of him,” they would not speak to Cutler again for several years. When Sam tried to speak for them, it went badly. The day the Stones flew home, San Francisco alternative FM favorite KSAN attempted to untangle the Altamont mess on a special call-in show. The exhausted Cutler was put on the air, but came off as defensive and dismissive. “…if people didn’t dig it, I’m sorry,” he said, sounding far more exasperated than apologetic.

An angry call from Hells Angels honcho Sonny Barger followed. Barger blamed the band and the crowd for the ugly turn of events, insisting that the Stones had duped the bikers and made them the fall guys for the free concert fiasco.

Sam Cutler lacked the funds, skills and connections to mount a public relations campaign. When he got word that the cops, the Hells Angels and potential plaintiffs’ lawyers were all looking for him, the street-smart Cutler vanished into the San Francisco underground. Many fans and journalists interpreted his silence as an admission of guilt.

Staying under the radar gave Cutler’s reputation a beating, but it may have saved him from a literal one—or something worse. Rumors that the revenge-hungry Hells Angels had put a price on Mick Jagger’s head were making the rounds. A motorcycle gang ordering a hit on a rock star sounds like the plot of a Roger Corman flick, or a tale cooked up by the Stone’s publicity obsessed former manager, Andrew Oldham. But during a 1983 U.S. Senate hearing on the criminal activities of outlaw bikers, a former Hells Angels testified that the gang still had an “open contract” on Jagger, and detailed two failed attempts to kill the singer.

Staying under the radar gave Cutler’s reputation a beating, but it may have saved him from a literal one—or something worse. Rumors that the revenge-hungry Hells Angels had put a price on Mick Jagger’s head were making the rounds. A motorcycle gang ordering a hit on a rock star sounds like the plot of a Roger Corman flick, or a tale cooked up by the Stone’s publicity obsessed former manager, Andrew Oldham. But during a 1983 U.S. Senate hearing on the criminal activities of outlaw bikers, a former Hells Angels testified that the gang still had an “open contract” on Jagger, and detailed two failed attempts to kill the singer.

A total of four people died at Altamont. Meredith Hunter was stabbed and stomped to death by the Hells Angels. Two concertgoers were killed by a hit-and-run driver. One accidently drowned in a drainage ditch. Ironically, the same number of people died at Woodstock, a fact that was lost in Woodstock’s overwhelmingly positive media coverage.

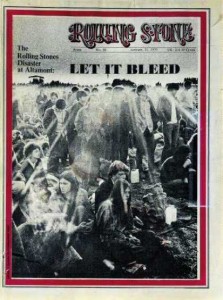

Initially, national coverage of Altamont was positive as well. Brief stories depicted the concert as a successful “Woodstock West” hampered by a few violent incidents. Then on January 21, 1970, Rolling Stone magazine ran an extensive cover story in which correspondents who had been on-site detailed the brutal reality of events on the ground.

Initially, national coverage of Altamont was positive as well. Brief stories depicted the concert as a successful “Woodstock West” hampered by a few violent incidents. Then on January 21, 1970, Rolling Stone magazine ran an extensive cover story in which correspondents who had been on-site detailed the brutal reality of events on the ground.

The article shined a light on the inept planning and ego clashes behind the show, then delivered withering critiques of the organizers, audience members, the Hells Angels and The Rolling Stones. A publication that had consistently heaped praise upon the band now excoriated them for letting things get so out of hand.

Rolling Stone was a countercultural touchstone, and the mainstream press quickly followed its lead. Altamont became an irresistible metaphor for the end of sixties and the death of the hippie dream.

The Rolling Stone piece got many things right. But it failed to mention that Ralph Gleason, publisher Jann Wenner’s mentor and one of the magazine’s founding editors, had been among the loudest voices demanding a free show in the first place. The Stones rock solid image as the hip, smart, cynical kings of the scene made it nearly impossible for any writer to suspect the truth: they were cash-strapped young men who had been trusting beyond the point of gullibility. Like everyone associated with Altamont, their biggest mistake was believing the myths of sixties’ San Francisco.

The deals that Tour Manager Ronnie Schneider structured to pull off the 1969 American tour changed the concert industry. So did Altamont. The lesson was clear. Woodstock was a fluke, not a model. A large show required a solid operating budget, extensive planning and a suitable venue with adequate access, parking, concessions, security, first aid, insurance, and more. Any concert that did not have those elements firmly in place invited disaster. Any free show that did not virtually guaranteed it.

The deals that Tour Manager Ronnie Schneider structured to pull off the 1969 American tour changed the concert industry. So did Altamont. The lesson was clear. Woodstock was a fluke, not a model. A large show required a solid operating budget, extensive planning and a suitable venue with adequate access, parking, concessions, security, first aid, insurance, and more. Any concert that did not have those elements firmly in place invited disaster. Any free show that did not virtually guaranteed it.

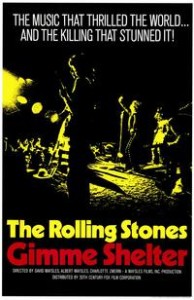

Having witnessed the horrors of Altamont firsthand, Ronnie Schneider realized that the Stones’ best defense likely lay in the footage shot by the Maysles brothers and their freelance crews. When David Maysles mentioned that he had enough material for a feature-length documentary, Schneider did a deal in minutes. The agreement was struck before the footage had been processed, and the two men had no way of knowing that the killing of Meredith Hunter had been caught on film.

Gimme Shelter opened in theatres on the first anniversary of Altamont. The movie captures the scope, complexity, violence and volatility of the event in harrowing detail. It also shows that—despite their generation’s belief in the power of rock stars—the Stones could not have solved everything by simply refusing to play, walking off mid-show, or bossing the crowd and the Angels around.

Gimme Shelter opened in theatres on the first anniversary of Altamont. The movie captures the scope, complexity, violence and volatility of the event in harrowing detail. It also shows that—despite their generation’s belief in the power of rock stars—the Stones could not have solved everything by simply refusing to play, walking off mid-show, or bossing the crowd and the Angels around.

The scene that clearly shows Meredith Hunter pulling a pistol bolstered the legal defense of the Angel who stabbed him to death. The jury ruled that Alan Passaro acted in self-defense. Meredith Hunter’s mother sued the Rolling Stones, and the matter was settled out-of-court for $10,000. Sam Cutler befriended Jerry Garcia and resurfaced as a co-manager of The Grateful Dead. Alan Passaro drowned under mysterious circumstances in 1985. The death appeared suspicious, but there was not enough evidence to declare foul play. Shades of Brian Jones.

Though Gimme Shelter softened criticisms of the Stones’ behavior at Altamont, the movie was attacked for profiting from the disaster. But by the time those criticisms arose, The Rolling Stones were desperately trying to escape from a very different kind of debacle.

(Click her to read Throwing Stones XXII: The Prince of Bankers, only on Bill’s BrainWorks!)

George B.

The Stones accidentally created their own version of Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side” and realized it too late. I had forgotten Altamont. Think the Stones have? Doubt it. Too many nights waking up in a cold sweat! It truly is amazing that these guys are still around to go on tour. Thanks for examining these historical events from so many views and angles–the good, the bad, and the waaay out there.

Dave

Best recount of Altamont I’ve ever read. Concise and compelling. And, perhaps most amazing, this piece really makes me want to see “Gimme Shelter.” No small feat, that. Bravo!

Elvis W.

I was also killed by bikers at Altamont… but I got better! Can you imagine anything related to the music business settling out of court for $10,000 these days? Nice job Bill!

Sadegh

Very entertaining and informative as always; lots of points I did not know.

Larry McC

When The Stones play Nashville next month, let’s hope that the only biker gangs that show up are riding the Tour de France models.

Debora G.

I’m shattered just reading this. The truth really is stranger than fiction. Glad you’re sticking the story for the long run!

Ro

This month the Belcourt Cinema showed Gimme Shelter. Missed that and will miss the Stones concert in town this summer as well. I guess I am dreaming that they would play the Ryman where the best music can be heard in lieu of tens of thousands of people paying to hear them. To me they are a great band. Sorry I missed seeing them play at Vanderbilt stadium for $35.00 many years ago.

WilliamSipt

Hello, I log on to your blog on a regular basis. Your story-telling style is witty, keep it up!

Legendario.