Throwing Stones IV: The Unmanageable Manager

(For Part III, click Throwing Stones III: Write Yer Own.)

In Part III, Andrew Loog Oldham, the Rolling Stones first manager, successfully badgered Mick Jagger and Keith Richards into writing songs, while writing some masterful PR of his own.

As Britain’s colonial empire vanished into history, a new empire built on entertainment appeared to be replacing it. Suddenly, British fiction, fashion, films, theatre, television and music were finding fans around the globe. Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham was the new English entertainment industry incarnate: the hippest manager in the U.K., a hotshot record producer and a partner in an ever-growing string of showbiz entities. A closer look reveals the cracks in young Andrew’s fab facade.

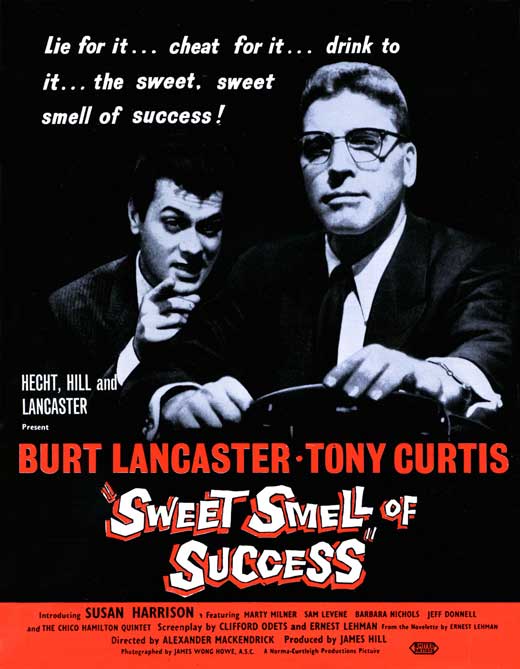

Oldham loved movies. He was obsessed with one in particular, the 1957 American noir potboiler Sweet Smell of Success. In the film, Burt Lancaster plays J.J. Hunsecker, a nationally syndicated gossip columnist with his own radio and TV show. The all-powerful Hunsecker is a ruthless bully who enjoys nothing more than ruining lives and destroying careers. His creepy fixation on his adult sister, combined with his hypocrisy, self-importance and twisted delight in blackmailing corrupt cops and desperate press agents into doing his dirtiest work make J.J. Hunsecker one of the most despicable characters in screen history. In fact, he’s number 36 on the AFI’s list of the greatest movie villains of all time.

Andrew Loog Oldham seems to have missed the point. Oldham fantasized about becoming the living embodiment of J.J. Hunsecker, and dreamed of a day when the entire entertainment world would bow before him or suffer accordingly. It was as if he had seen Shane and mistaken Jack Palance’s psychotic gunslinger for the hero.

Oldham’s business relationships tended to degenerate into grudge matches with astonishing speed. Oldham and Stones co-manager and booker Eric Easton fell out in short order. Oldham claimed Easton was a sneaky old fuddy-duddy who envied his youth and celebrity, cheated him out of his fair share of commissions and demanded kickbacks on the band’s live gigs. Easton’s defenders, who include Bill Wyman, saw Easton as an honest old-timer who quickly tired of Oldham’s inflated ego, erratic behavior, and focus on his own fame.

Rather than sort out matters with his partner, Oldham threw himself into another venture. And then another. A pattern soon developed. Whenever Oldham got into a dispute with a partner in one company, he found another partner and started another company, creating a trail of dysfunctional businesses and unresolved issues.

Ignoring Easton’s advice that a manager should never get too close to his clients, Oldham moved in with Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. He stuck close to his lads, enjoying all the perks of a rising rock star. The young Stones were a magnet for sex, drugs and booze, and Andrew Oldham was in no mood to say no to any of the above.

Oldham started producing instrumental versions of Stones’ numbers, employing his new roomies as session players. Jagger and Richards appreciated the extra income, as did Oldham, who had no qualms about using his “Andrew Oldham Orchestra” tracks as B-sides of singles he produced for other artists. It was a trick Oldham had learned from his idol, Phil Spector. The fact that a B-side credited to a different act than the artist on the A-side might confuse young record buyers and would deny the artist the easy income gained from a flipside didn’t bother Oldham.

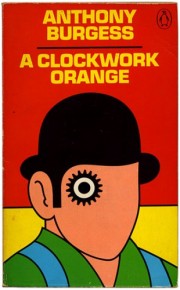

Oldham soon set about turning his Sweet Smell of Success fantasies into reality. Making matters worse, he added a dose of the droogs, the brutal young gang in Anthony Burgess’ 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange. Alex, the book’s narrator, enjoys committing random acts of violence to entertain himself and his friends. Once again, Oldham made a fictional fiend into a personal hero. (Oldham tried to option the book and cast the Rolling Stones as the gang, but someone else had the film rights sewn up. Stanley Kubrick would eventually direct, sans Stones.)

Oldham hired a handsome sociopath named Reg to serve as his chauffeur. Reg’s real job was to intimidate or physically attack anyone Oldham imagined had crossed him. One of Oldham’s favorite past times involved instructing Reg edge alongside another car at a traffic light. When the light changed, Oldham would lean out and punch the stranger in the car beside his, then order Reg to speed them from the scene.

Oldham hired a handsome sociopath named Reg to serve as his chauffeur. Reg’s real job was to intimidate or physically attack anyone Oldham imagined had crossed him. One of Oldham’s favorite past times involved instructing Reg edge alongside another car at a traffic light. When the light changed, Oldham would lean out and punch the stranger in the car beside his, then order Reg to speed them from the scene.

Oldham continues to lovingly recount the day he tired of a young music reporter’s remarks about Keith Richards’ pimples. Andrew and Reg burst into the reporter’s office, jammed the man’s hands beneath an open window and threatened to crush them if the writer ever typed another word about the guitarist’s acne.

Andrew’s amateur gangster antics would have been shut down with brutal efficiency (and most likely, efficient brutality) in the mobbed-up American music business of the 1960s. But the stuffy old sirs who ran English show business had no idea what to make of Oldham’s third-rate thuggery.

As his mania for drink, drugs and delusions of grandeur spun out of control, Andrew Loog Oldham failed to notice that Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were growing annoyed with his behavior. Though they had once found Oldham’s shenanigans amusing, Jagger in particular was developing a keen sense of what it took to succeed in show business, and the singer began to regardi his band’s wunderkind manager/producer as more of a liability than an asset. Oldham should have re-read A Clockwork Orange and taken note of the scene in which the droogs finally tire of Alex’s high-handed self-regard and decide they’d rather run the show themselves.

(This concludes Part IV. To read Part V, click Throwing Stones V: The Uncanny Accountant.)

Andrew Loog Oldham is bipolar, and had become depressed over the Stones’ lack of new material well before the session. Dejected, Oldham excused himself and took a brief walk, desperately trying to think of a solution. In perhaps the most incredible stroke of luck in pop music history, he bumped into John Lennon and Paul McCartney. The two songwriters stepped out of a handsome cab, having just left a Variety Club Luncheon honoring the Beatles. Full of free booze and good cheer, they immediately sensed their friend’s distress. When Oldham explained his dilemma, they responded with what can only be called Beatlesque enthusiasm. No song? No problem! They had a new number that was perfect for the Stones!

Andrew Loog Oldham is bipolar, and had become depressed over the Stones’ lack of new material well before the session. Dejected, Oldham excused himself and took a brief walk, desperately trying to think of a solution. In perhaps the most incredible stroke of luck in pop music history, he bumped into John Lennon and Paul McCartney. The two songwriters stepped out of a handsome cab, having just left a Variety Club Luncheon honoring the Beatles. Full of free booze and good cheer, they immediately sensed their friend’s distress. When Oldham explained his dilemma, they responded with what can only be called Beatlesque enthusiasm. No song? No problem! They had a new number that was perfect for the Stones!

Oldham figured if Lennon and McCartney could write hits, so could Jagger and Richard(s). He floated the idea. Mick and Keith torpedoed it. They were performers, not song poets. Oldham pressed the issue. Bands that couldn’t come up with original material had no future. And they certainly couldn’t expect the petulant and increasingly unreliable Brian Jones to deliver. If the Rolling Stones wanted to hang onto their newfound fame, Jagger and Richards had better get started. The reluctant duo eventually agreed, but made little progress.

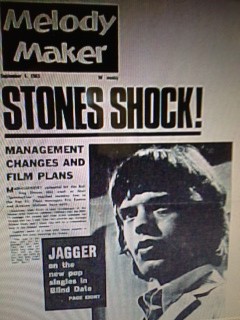

Oldham figured if Lennon and McCartney could write hits, so could Jagger and Richard(s). He floated the idea. Mick and Keith torpedoed it. They were performers, not song poets. Oldham pressed the issue. Bands that couldn’t come up with original material had no future. And they certainly couldn’t expect the petulant and increasingly unreliable Brian Jones to deliver. If the Rolling Stones wanted to hang onto their newfound fame, Jagger and Richards had better get started. The reluctant duo eventually agreed, but made little progress. While Jagger and Richards were busy writing songs, Andrew Loog Oldham was busy writing prose. Oldham’s PR masterpiece was the soon-to-be-infamous line, “Would You Let Your Daughter Go With A Rolling Stone?” Oldham fed his grabber to Melody Maker magazine, where a teen-centric editor changed “Daughter” to “Sister” and ran it as a headline. The stuffy Fleet Street editors who ruled the mainstream press weren’t exactly sure what “Go” implied, so they changed it to “Would You Let Your Daughter Marry A Rolling Stone?” and turned it into a legend. “The headline was a great example of everlasting meaning via product placement,” Oldham would write, decades later.

While Jagger and Richards were busy writing songs, Andrew Loog Oldham was busy writing prose. Oldham’s PR masterpiece was the soon-to-be-infamous line, “Would You Let Your Daughter Go With A Rolling Stone?” Oldham fed his grabber to Melody Maker magazine, where a teen-centric editor changed “Daughter” to “Sister” and ran it as a headline. The stuffy Fleet Street editors who ruled the mainstream press weren’t exactly sure what “Go” implied, so they changed it to “Would You Let Your Daughter Marry A Rolling Stone?” and turned it into a legend. “The headline was a great example of everlasting meaning via product placement,” Oldham would write, decades later. t Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein was nothing if not persistent, and as 1961 entered the history books, he had exciting New Year’s news for his unsigned band: They had a shot at a contract with Decca records. Decca would ultimately pass on the Beatles with the soon-to-be-infamous line, “Guitar groups are on their way out.” A year later, the Beatles were a chart-storming sensation, and Decca Records was the laughingstock of the industry.

t Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein was nothing if not persistent, and as 1961 entered the history books, he had exciting New Year’s news for his unsigned band: They had a shot at a contract with Decca records. Decca would ultimately pass on the Beatles with the soon-to-be-infamous line, “Guitar groups are on their way out.” A year later, the Beatles were a chart-storming sensation, and Decca Records was the laughingstock of the industry. Lucky for Decca, George Harrison didn’t hold a grudge. While appearing on the TV show “Jukebox Jury,” Harrison told fellow guest-judge and Decca A&R Director Dick Rowe about a great new band. A rockin’ R&B outfit called The Rollin’ Stones. Having blown his shot at the Beatles, Rowe wasn’t about to ignore Harrison’s hot tip.

Lucky for Decca, George Harrison didn’t hold a grudge. While appearing on the TV show “Jukebox Jury,” Harrison told fellow guest-judge and Decca A&R Director Dick Rowe about a great new band. A rockin’ R&B outfit called The Rollin’ Stones. Having blown his shot at the Beatles, Rowe wasn’t about to ignore Harrison’s hot tip. made it to the middle of the British Top 40. It was a respectable showing, but the follow-up had Oldham flummoxed.

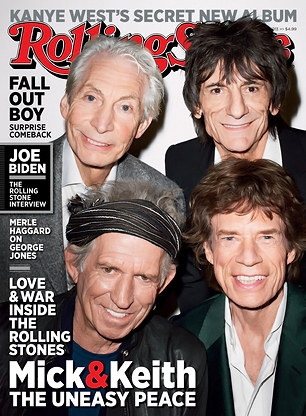

made it to the middle of the British Top 40. It was a respectable showing, but the follow-up had Oldham flummoxed. Before you accuse me of being jaded, get a gander at the May 23rd issue of Rolling Stone magazine, which, to absolutely no one’s surprise, features the band on the cover. Again. Meanwhile, the article inside sheepishly reports that a ticket for the gang’s latest go ’round starts, that’s right, starts, at $150 and spirals upward to somewhere north of $2000. With prices like these, who needs scalpers?

Before you accuse me of being jaded, get a gander at the May 23rd issue of Rolling Stone magazine, which, to absolutely no one’s surprise, features the band on the cover. Again. Meanwhile, the article inside sheepishly reports that a ticket for the gang’s latest go ’round starts, that’s right, starts, at $150 and spirals upward to somewhere north of $2000. With prices like these, who needs scalpers? Like it or not, we live in an era in which the terms “band” and “brand” have become interchangeable. An era in which the Rolling Stones will continue to be awarded iconic status. Ironic might be more suitable. Because, contrary to the fundamental tenants of marketing, the longer the Stones continue as a band, the more they damage their brand.

Like it or not, we live in an era in which the terms “band” and “brand” have become interchangeable. An era in which the Rolling Stones will continue to be awarded iconic status. Ironic might be more suitable. Because, contrary to the fundamental tenants of marketing, the longer the Stones continue as a band, the more they damage their brand. By positioning the Rolling Stones as the anti-Beatles and relentlessly flogging their rebellious image, Oldham defined the Stone’s public perception for decades. The Stones, for their part, were more than happy to play along. They fancied themselves an authentic Chicago blues band—the kind of willful denial of reality that only teenagers in their first rock group or someone with a serious head injury can muster—and dreaded being sold as suit-wearing sunshine boys. Besides, just as being sly, witty and charming came naturally to the Beatles, being snotty, scrappy and scruffy came naturally to the Rolling Stones. Going with Oldham’s flow was an assignment they could handle.

By positioning the Rolling Stones as the anti-Beatles and relentlessly flogging their rebellious image, Oldham defined the Stone’s public perception for decades. The Stones, for their part, were more than happy to play along. They fancied themselves an authentic Chicago blues band—the kind of willful denial of reality that only teenagers in their first rock group or someone with a serious head injury can muster—and dreaded being sold as suit-wearing sunshine boys. Besides, just as being sly, witty and charming came naturally to the Beatles, being snotty, scrappy and scruffy came naturally to the Rolling Stones. Going with Oldham’s flow was an assignment they could handle.

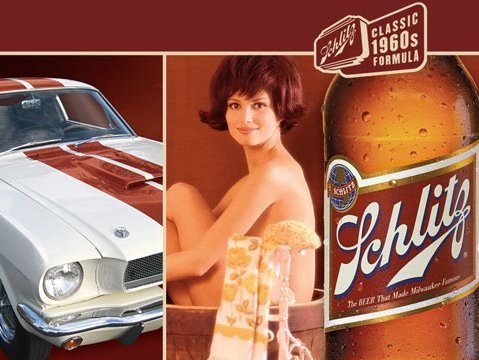

names or street addresses. As “Classic 60’s Formula” Schlitz struggles, Yuengling has become the cool American lager of the moment, siphoning off the buzz that Schlitz had hoped to call its own.

names or street addresses. As “Classic 60’s Formula” Schlitz struggles, Yuengling has become the cool American lager of the moment, siphoning off the buzz that Schlitz had hoped to call its own.

Meanwhile, my calls to Schlitz have gone unreturned. Still, if I can find a bottle of their new-old formula, I’ll gladly give it a go. The folks who brew Schlitz have tried to do the right thing, and for that alone, the brand deserves a shot. Who knows? Decades after it disappeared, now may be the time to give Gusto another chance.

Meanwhile, my calls to Schlitz have gone unreturned. Still, if I can find a bottle of their new-old formula, I’ll gladly give it a go. The folks who brew Schlitz have tried to do the right thing, and for that alone, the brand deserves a shot. Who knows? Decades after it disappeared, now may be the time to give Gusto another chance. Fast forward to 2007. Pabst Brewing had been sold several times, eventually morphing into a holding company that owned several beer brands, including Pabst Blue Ribbon, Schlitz, Stroh’s, Old Milwaukee and more. The company contracts out the production of these beers, operating no breweries of its own.

Fast forward to 2007. Pabst Brewing had been sold several times, eventually morphing into a holding company that owned several beer brands, including Pabst Blue Ribbon, Schlitz, Stroh’s, Old Milwaukee and more. The company contracts out the production of these beers, operating no breweries of its own.

Other things had changed as well. Wine had gone mainstream. Hard liquor was back, inspiring expensive, super-premium products and a cocktail craze. And all of the famous American breweries founded by German immigrants in the 1800s had been swallowed by conglomerates.

Other things had changed as well. Wine had gone mainstream. Hard liquor was back, inspiring expensive, super-premium products and a cocktail craze. And all of the famous American breweries founded by German immigrants in the 1800s had been swallowed by conglomerates. into his fridge and stealing his last six-pack. Thunderstruck viewers felt like the town bully had gone on a bender and busted into their living rooms in a beer-fueled rage. The nerve! After all, they hadn’t messed with this psycho’s Schlitz; Schlitz had messed with his Schlitz!

into his fridge and stealing his last six-pack. Thunderstruck viewers felt like the town bully had gone on a bender and busted into their living rooms in a beer-fueled rage. The nerve! After all, they hadn’t messed with this psycho’s Schlitz; Schlitz had messed with his Schlitz! Unlike Schlitz, PBR had not been reformulated. But its image had. As Schlitz self-destructed, Blue Ribbon’s decline took a steep turn for the worse. The brand never recovered. Tellingly, the “popular price” beer category eventually came to be known as the “sub-premium” category.

Unlike Schlitz, PBR had not been reformulated. But its image had. As Schlitz self-destructed, Blue Ribbon’s decline took a steep turn for the worse. The brand never recovered. Tellingly, the “popular price” beer category eventually came to be known as the “sub-premium” category. Blue Ribbon’s dive and Schlitz’s suicide had Miller looking like a sure thing. Certain that Anheuser-Busch’s golden boy was on the ropes, Phillip Morris execs moved in for the win. They didn’t realize the easy part was over.

Blue Ribbon’s dive and Schlitz’s suicide had Miller looking like a sure thing. Certain that Anheuser-Busch’s golden boy was on the ropes, Phillip Morris execs moved in for the win. They didn’t realize the easy part was over. The baby boomers lack of enthusiasm for hard liquor was a boon to America’s beer makers. But while both the Joseph Schlitz and Anheuser-Busch brewing companies were hugely successful, neither was outrageously profitable. Brewing is an expensive process that requires a unique combination of high quality ingredients and time. Shortchanging either is risky business.

The baby boomers lack of enthusiasm for hard liquor was a boon to America’s beer makers. But while both the Joseph Schlitz and Anheuser-Busch brewing companies were hugely successful, neither was outrageously profitable. Brewing is an expensive process that requires a unique combination of high quality ingredients and time. Shortchanging either is risky business. re-orgs.

re-orgs. For three-quarters of the twentieth century, two great brands stood toe-to-toe and slugged it out for the heavyweight title of America’s most popular beer. Then, to the astonishment of its loyal fans, one took off the gloves and pounded itself into oblivion in a few short rounds.

For three-quarters of the twentieth century, two great brands stood toe-to-toe and slugged it out for the heavyweight title of America’s most popular beer. Then, to the astonishment of its loyal fans, one took off the gloves and pounded itself into oblivion in a few short rounds. A wide-ranging array of restaurants offered a taste of their wares, including old favorites like Sunset Grill, Tin Angel and Merchants, more recent arrivals like Table 3 and The Pharmacy, and corporate big guns like Aquarium and Rainforest Café. The list is far too long to mention all of them here, though not quite long enough to have kept me from stuffing myself with samples from nearly every station.

A wide-ranging array of restaurants offered a taste of their wares, including old favorites like Sunset Grill, Tin Angel and Merchants, more recent arrivals like Table 3 and The Pharmacy, and corporate big guns like Aquarium and Rainforest Café. The list is far too long to mention all of them here, though not quite long enough to have kept me from stuffing myself with samples from nearly every station. My hopes that Sue would have a sister along were answered by “Hap & Harry’s® Lynchburg Lager.” This isa refreshing entry with a slight sweetness and a crisp finish, brewed by Yazoo in partnership with Tennessee distributor R.S. Lipman. It’s a beer that every Yuengling lover could love, and one whose local charm could easily end a romance with the pride of Pennsylvania.

My hopes that Sue would have a sister along were answered by “Hap & Harry’s® Lynchburg Lager.” This isa refreshing entry with a slight sweetness and a crisp finish, brewed by Yazoo in partnership with Tennessee distributor R.S. Lipman. It’s a beer that every Yuengling lover could love, and one whose local charm could easily end a romance with the pride of Pennsylvania. A forgotten American favorite, rye whiskey is distinguished by a mash bill in which rye, rather than corn, is the dominant grain. Typically viewed as bourbon’s bolder, spicier cousin, rye whiskey began making a comeback in the early 2000s. Today, stores that once struggled to scrounge up a bottle of Old Overholt® offer an ever-growing list of ryes in a range of prices. Though announced last fall, George Dickel Rye has just started showing up on many stores’ shelves. It’s a welcome addition, combining the spice and citrus notes one expects in a rye with a sweet smoothness that makes for easy sippin’, even at 90 proof.

A forgotten American favorite, rye whiskey is distinguished by a mash bill in which rye, rather than corn, is the dominant grain. Typically viewed as bourbon’s bolder, spicier cousin, rye whiskey began making a comeback in the early 2000s. Today, stores that once struggled to scrounge up a bottle of Old Overholt® offer an ever-growing list of ryes in a range of prices. Though announced last fall, George Dickel Rye has just started showing up on many stores’ shelves. It’s a welcome addition, combining the spice and citrus notes one expects in a rye with a sweet smoothness that makes for easy sippin’, even at 90 proof. Collier and McKeel® Tennessee Whiskey, meanwhile, was being made just a few miles from where westood. A taste quickly revealed that Collier and McKeel is no Dickel or Daniel’s knockoff. Though corn dominates its mash bill, a helping of rye gives this small batch upstart a spicier taste than other Tennessee Whiskies, while charcoal filtering keeps things smooth. If you like American whiskies, but have a hard time deciding between bourbon, rye and Tennessee whiskey, Collier and McKeel may be the ideal resolution to your dilemma.

Collier and McKeel® Tennessee Whiskey, meanwhile, was being made just a few miles from where westood. A taste quickly revealed that Collier and McKeel is no Dickel or Daniel’s knockoff. Though corn dominates its mash bill, a helping of rye gives this small batch upstart a spicier taste than other Tennessee Whiskies, while charcoal filtering keeps things smooth. If you like American whiskies, but have a hard time deciding between bourbon, rye and Tennessee whiskey, Collier and McKeel may be the ideal resolution to your dilemma.