Throwing Stones XVII: You Gotta’ Move

(This is Part XVII. Click here to read Throwing Stones Part XVI: Highway ’69 Revisited)

In Part XVI, The Rolling Stones returned to America for the first time in three years, mounting a triumphant tour on a shoestring budget.

The Rolling Stones arrived at Muscle Shoals Sound Studios in Sheffield, Alabama, on December 2, 1969. Over the course of three days, they cut “Brown Sugar,” “Wild Horses” and a cover of “You Gotta’ Move,” a spiritual recorded by numerous American blues and gospel artists. The Stones didn’t have work permits to record in the states and didn’t want their estranged manager, Allen Klein, to know what they were up to, so their session in the sticks had been scheduled on the sly. It quickly became the worst kept secret in rock ’n’ roll.

The band’s contracts with Klein and Decca Records would be expiring soon. Ahmet Ertegun, famed head of Atlantic Records, flew in to discuss the formation of Rolling Stones Records, a label that would be owned by the band and distributed by Atlantic. Meanwhile, on the other side of the country, the Stones’ employees were scrambling to pull off their promised free concert.

The band’s contracts with Klein and Decca Records would be expiring soon. Ahmet Ertegun, famed head of Atlantic Records, flew in to discuss the formation of Rolling Stones Records, a label that would be owned by the band and distributed by Atlantic. Meanwhile, on the other side of the country, the Stones’ employees were scrambling to pull off their promised free concert.

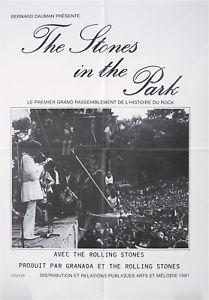

Various San Francisco bands had staged successful free shows in Golden Gate Park. Word quickly spread that, with the help of The Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane, the Stones would soon play the park’s biggest bash yet—San Francisco’s own “Woodstock West.” But the free show seemed snake-bit from the start.

Various San Francisco bands had staged successful free shows in Golden Gate Park. Word quickly spread that, with the help of The Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane, the Stones would soon play the park’s biggest bash yet—San Francisco’s own “Woodstock West.” But the free show seemed snake-bit from the start.

Fans were baffled when formerly cooperative city officials refused to issue the necessary permits. While some said the change of heart was due to old tensions between hippies and the police, rumors spread that concert promoter Bill Graham had convinced authorities to scuttle the show.

The Stones had infuriated Graham by rejecting his offer to handle their entire American tour. The pugnacious promoter had to settle for a single Bay Area gig instead. Bill Graham had an ego as big as any rockstar’s, and he never forgot a slight. When The Rolling Stones arrived at the Oakland Coliseum in November of 1969, they were greeted by a large photo of Graham giving them the finger, hung over the backstage buffet. Things went downhill from there.

The Stones had infuriated Graham by rejecting his offer to handle their entire American tour. The pugnacious promoter had to settle for a single Bay Area gig instead. Bill Graham had an ego as big as any rockstar’s, and he never forgot a slight. When The Rolling Stones arrived at the Oakland Coliseum in November of 1969, they were greeted by a large photo of Graham giving them the finger, hung over the backstage buffet. Things went downhill from there.

The Stones and their entourage pelted the photo with food. A shouting match with Graham ensued. The two sides came to blows after the promoter and his security goons began taking their frustrations out on the fans, and Charlie Watts saw Graham slap a teenage girl. The show did eventually go on, but the bad blood remained.

Bill Graham was making a fortune by monetizing the Bay Area music scene, ruthlessly eliminating the flower power competition that had nurtured it to life. Torpedoing a free Stones gig would have allowed him to protect his turf while taking revenge on the band, but evidence that he actually did remains anecdotal.

With the park off limits, Hollywood rode to the rescue. Filmways—the production company responsible for a string of hit TV shows, includingThe Beverly Hillbillies, Green Acres and Hollywood Squares—had recently purchased the Sears Point Raceway. The company generously offered the track as a venue for the free show, with the stipulation that the band would have to pay a few thousand dollars to cover the cost of an insurance rider. Close to San Francisco and less than a year old, the Sears Point facility was an ideal solution. All parties agreed to a December 6 date. Stage and Lighting Designer Chip Monck and his crew began setting up the stage, lighting and sound system.

Then the corporate execs pulled a fast one, demanding a huge pre-show payment (the reported number ranges from $100,000 to $450,000 to $6 million) to cover insurance, clean up and other costs. What’s more, they insisted the Stones sign over all film and video rights free of charge.

With staging under construction and thousands of fans from around the country en route, the Hollywood hotshots must have figured their squeeze play was a sure thing. They had no clue that the Rolling Stones were nearly broke, or that Allen Klein, who was sitting on the bulk of the Stones’ fortune, would never surrender such a potentially lucrative copyright. Abandoning Sears Point was the band’s only option.

With staging under construction and thousands of fans from around the country en route, the Hollywood hotshots must have figured their squeeze play was a sure thing. They had no clue that the Rolling Stones were nearly broke, or that Allen Klein, who was sitting on the bulk of the Stones’ fortune, would never surrender such a potentially lucrative copyright. Abandoning Sears Point was the band’s only option.

Still, neither Jagger nor Richards was willing to give up on the free show. Tour Manager Ronnie Schneider decided they needed legal help to pull it off, and enlisted legendary San Francisco attorney Melvin Belli in the cause. As is the case with many of the people the Stones encountered during their storied career, calling the lawyer a colorful character hardly does him justice.

Belli’s effectiveness in personal injury cases had earned him the nickname “The King of Torts” His opponents preferred “Melvin Bellicose.” His long list of celebrity clients included Mae West, Muhammad Ali and Tony Curtis. Belli had even defended Jack Ruby when the Texan was tried for killing Lee Harvey Oswald—a murder broadcast live on national television.

Belli’s effectiveness in personal injury cases had earned him the nickname “The King of Torts” His opponents preferred “Melvin Bellicose.” His long list of celebrity clients included Mae West, Muhammad Ali and Tony Curtis. Belli had even defended Jack Ruby when the Texan was tried for killing Lee Harvey Oswald—a murder broadcast live on national television.

A pioneer of the class action lawsuit, Belli was well-known, well-connected and very well off. Long before the skull and crossbones flew over Apple headquarters, Belli famously ran the Jolly Roger up the flagpole atop his Barbary Coast office building every time he won a case. Adding a flourish that even Steve Jobs did not dare duplicate, Belli fired a celebratory cannon shot as well.

Though he was a preening, egomaniacal dandy, Belli was also an immensely charming raconteur with an impressive ability to sway opinions and get things done. And he was more than happy to pull strings for The Rolling Stones.

Sears Point wasn’t the only Northern California racetrack under new ownership. Dick Carter, a middle aged Bay Area businessman, had recently purchased the Altamont Speedway, located 90 miles northeast of San Francisco near the small town of Livermore. Drivers loved the track, but it had struggled financially since opening in the summer of ’66. Altamont seemed to be just a little too far from everywhere to be successful.

Dick Carter was hungry to publicize Altamont, and when he heard a free rock festival was looking for a venue, he jumped at the chance, offering the track at no charge. In a crowded meeting at Melvin Belli’s office with Carter and the press in attendance, Belli deftly brushed past concerns expressed by authorities in a conference call.

“Woodstock West” had found a home at last. Altamont was on.

(This concludes Part XVII. Click now to read Part XVIII: Merciless Angels!)

The William Morris Agency was in the final stages of nailing down a deal to book the tour when Klein butted heads with the band. Ronnie Schneider snowed the Morris agents, telling them he was going with a different firm. Having finally learned the value of rock ’n’ roll, William Morris was desperate to hang on to the year’s hottest tour. They agreed to cut their commission in half and put up $15,000 of funding.

The William Morris Agency was in the final stages of nailing down a deal to book the tour when Klein butted heads with the band. Ronnie Schneider snowed the Morris agents, telling them he was going with a different firm. Having finally learned the value of rock ’n’ roll, William Morris was desperate to hang on to the year’s hottest tour. They agreed to cut their commission in half and put up $15,000 of funding.

Initially, Klein had been generous with the Stones, doling out large sums of money with a smile. In 1966, when Keith Richards inquired if he could afford to buy a home in one of London’s toniest neighborhoods, Klein cut the guitarist a check for the full purchase price. But as time went by, the checkbook tightened, and Mick Jagger in particular began to suspect that their wily manager was getting the best of the Stones’ business deals.

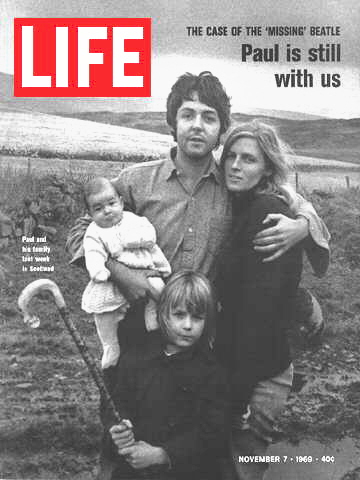

Initially, Klein had been generous with the Stones, doling out large sums of money with a smile. In 1966, when Keith Richards inquired if he could afford to buy a home in one of London’s toniest neighborhoods, Klein cut the guitarist a check for the full purchase price. But as time went by, the checkbook tightened, and Mick Jagger in particular began to suspect that their wily manager was getting the best of the Stones’ business deals. After splitting with actress Jane Asher, Paul McCartney had fallen in love with Linda Eastman, a young American photographer. Contrary to still-popular rumors, Linda Eastman was not the heir to the Eastman-Kodak fortune. But she was from a wealthy New York family. Linda’s father, Lee Eastman, was one of the world’s top intellectual property lawyers, and had decades of entertainment industry experience. Linda’s brother, John, had recently joined her father’s practice.

After splitting with actress Jane Asher, Paul McCartney had fallen in love with Linda Eastman, a young American photographer. Contrary to still-popular rumors, Linda Eastman was not the heir to the Eastman-Kodak fortune. But she was from a wealthy New York family. Linda’s father, Lee Eastman, was one of the world’s top intellectual property lawyers, and had decades of entertainment industry experience. Linda’s brother, John, had recently joined her father’s practice.

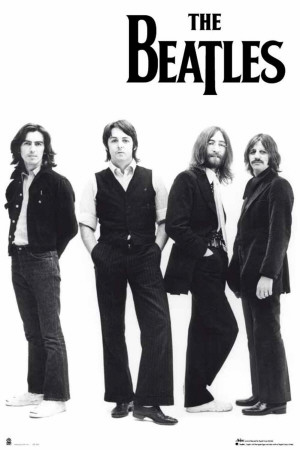

When the four Beatles sat down to decide who would manage the band and handle the turnaround at Apple, Allen Klein got three votes. The Eastmans got one. The Fab Four had a standing rule that all significant decisions had to be unanimous, and McCartney was shocked to hear his bandmates insist that the rule was no longer valid—Klein had won by majority and that was that. It was the beginning of the end.

When the four Beatles sat down to decide who would manage the band and handle the turnaround at Apple, Allen Klein got three votes. The Eastmans got one. The Fab Four had a standing rule that all significant decisions had to be unanimous, and McCartney was shocked to hear his bandmates insist that the rule was no longer valid—Klein had won by majority and that was that. It was the beginning of the end. James announced that he was selling his interest to ATV Entertainment, a conglomerate owned by Lord Lew Grade, a cigar-chomping British showbiz mogul. The Beatles felt utterly betrayed. Klein promised to stop the sale. But neither Klein nor the Eastmans were able to prevent it, especially after a frustrated John Lennon foolishly threw a tantrum in a critical meeting and denounced a group of potential white knight co-investors as just another bunch of greedy businessmen.

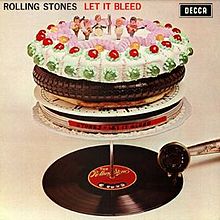

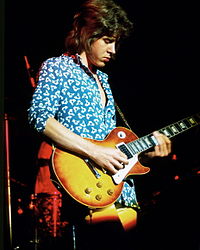

James announced that he was selling his interest to ATV Entertainment, a conglomerate owned by Lord Lew Grade, a cigar-chomping British showbiz mogul. The Beatles felt utterly betrayed. Klein promised to stop the sale. But neither Klein nor the Eastmans were able to prevent it, especially after a frustrated John Lennon foolishly threw a tantrum in a critical meeting and denounced a group of potential white knight co-investors as just another bunch of greedy businessmen. But what of The Rolling Stones? Unlike their Liverpool pals, Jagger and Richards’ outfit was firing on all cylinders. The addition of guitarist Mick Taylor had turbocharged their most creative period. Their rollicking summer single, “Honky Tonk Women,” spent weeks at number one on both the U.S. and U.K. charts. The band’s first U.S. tour in over three years was penciled in for the fall, along with another appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. A new album was scheduled for release as soon as the tour wrapped. The Stones had even decided to title the LP “Let It Bleed,” in sly mockery of their rivals’ (as yet unreleased) “Let It Be.”

But what of The Rolling Stones? Unlike their Liverpool pals, Jagger and Richards’ outfit was firing on all cylinders. The addition of guitarist Mick Taylor had turbocharged their most creative period. Their rollicking summer single, “Honky Tonk Women,” spent weeks at number one on both the U.S. and U.K. charts. The band’s first U.S. tour in over three years was penciled in for the fall, along with another appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. A new album was scheduled for release as soon as the tour wrapped. The Stones had even decided to title the LP “Let It Bleed,” in sly mockery of their rivals’ (as yet unreleased) “Let It Be.” In 1967, Klein acquired Cameo Records and its subsidiary label, Parkway. Founded in Philadelphia in 1956, Cameo had reaped huge benefits from being based in the same city as American Bandstand, Dick Clark’s nationally broadcast TV teen-dance sensation. Booking Cameo-Parkway artists on Bandstand was easy, and whenever Clark got in a pinch or needed a fill-in for a cancellation, Cameo-Parkway got the call.

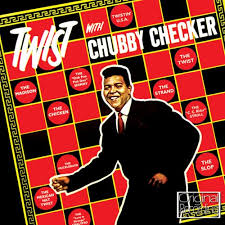

In 1967, Klein acquired Cameo Records and its subsidiary label, Parkway. Founded in Philadelphia in 1956, Cameo had reaped huge benefits from being based in the same city as American Bandstand, Dick Clark’s nationally broadcast TV teen-dance sensation. Booking Cameo-Parkway artists on Bandstand was easy, and whenever Clark got in a pinch or needed a fill-in for a cancellation, Cameo-Parkway got the call. Though Cameo-Parkway had a number of hits, it is best known for Chubby Checker’s version of “The Twist,” which topped the U.S. charts in both 1960 and 1962, inspiring a long-running nationwide dance craze.

Though Cameo-Parkway had a number of hits, it is best known for Chubby Checker’s version of “The Twist,” which topped the U.S. charts in both 1960 and 1962, inspiring a long-running nationwide dance craze. MGM Records purchased Cameo-Parkway in 1967. MGM then sold the struggling label to Klein, who was a major MGM stockholder. Klein restructured his own company as ABKCO, which he jokingly claimed was an acronym for “A Better Kind of Company.” It actually stood for “Allen & Betty Klein & Company.” (Betty was Klein’s wife.) ABKCO obtained the master recording catalogs of MGM artists Herman’s Hermits and The Animals from producer Mickie Most. But Allen Klein was far from satisfied. He was playing the long game, and had set his sights on the biggest act in show biz: The Beatles.

MGM Records purchased Cameo-Parkway in 1967. MGM then sold the struggling label to Klein, who was a major MGM stockholder. Klein restructured his own company as ABKCO, which he jokingly claimed was an acronym for “A Better Kind of Company.” It actually stood for “Allen & Betty Klein & Company.” (Betty was Klein’s wife.) ABKCO obtained the master recording catalogs of MGM artists Herman’s Hermits and The Animals from producer Mickie Most. But Allen Klein was far from satisfied. He was playing the long game, and had set his sights on the biggest act in show biz: The Beatles.

The Beatles had big dreams for Apple, and new divisions, including music publishing and consumer electronics, were added. Despite the success of the record division, Apple quickly became a financial sinkhole. Too many friends and hangers on were being paid too much to do too little. Every new idea, no matter how impractical, seemed to be funded ad absurdum. Ridiculous expenses like a fully stocked, in-house wine cellar and on-staff chefs were common.

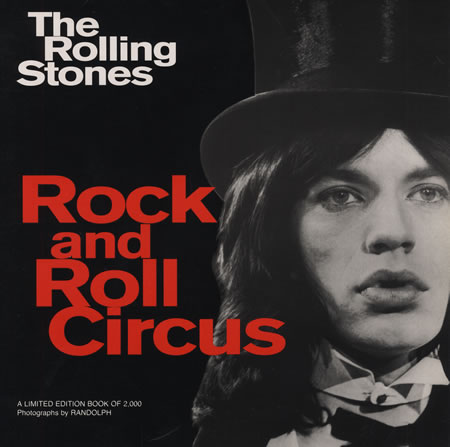

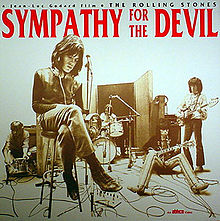

The Beatles had big dreams for Apple, and new divisions, including music publishing and consumer electronics, were added. Despite the success of the record division, Apple quickly became a financial sinkhole. Too many friends and hangers on were being paid too much to do too little. Every new idea, no matter how impractical, seemed to be funded ad absurdum. Ridiculous expenses like a fully stocked, in-house wine cellar and on-staff chefs were common. That same December, John and Yoko were guests on The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus, a star-studded TV special that remained unseen until 1996 due to music licensing issues and the Stones unhappiness with their own performance. During the taping, Klein introduced himself to Lennon, humbly describing himself as “an accountant.” Lennon responded positively, saying that he feared ending up broke like American movie star Mickey Rooney. Klein’s face lit up.

That same December, John and Yoko were guests on The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus, a star-studded TV special that remained unseen until 1996 due to music licensing issues and the Stones unhappiness with their own performance. During the taping, Klein introduced himself to Lennon, humbly describing himself as “an accountant.” Lennon responded positively, saying that he feared ending up broke like American movie star Mickey Rooney. Klein’s face lit up.

By 1969, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were eager to get the Rolling Stones back on the road. The music boom that had begun with Beatlemania showed no signs of stopping, and rock concerts were becoming very big business. A savvy new breed of promoters, epitomized by San Francisco’s Bill Graham, realized just how much money there was to be made, and began offering unprecedented paydays to popular acts.

By 1969, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were eager to get the Rolling Stones back on the road. The music boom that had begun with Beatlemania showed no signs of stopping, and rock concerts were becoming very big business. A savvy new breed of promoters, epitomized by San Francisco’s Bill Graham, realized just how much money there was to be made, and began offering unprecedented paydays to popular acts.

Given the fallout of their own drug bust, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards had been supportive of Brian Jones. But as tour offers mounted and Jones declined, their attitude grew cold. Jagger even referred to Jones as “a wooden leg” during a newspaper interview. Unbeknownst to Jones, the band began recording with Mick Taylor, a masterful young guitarist who had cut his teeth with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers.

Given the fallout of their own drug bust, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards had been supportive of Brian Jones. But as tour offers mounted and Jones declined, their attitude grew cold. Jagger even referred to Jones as “a wooden leg” during a newspaper interview. Unbeknownst to Jones, the band began recording with Mick Taylor, a masterful young guitarist who had cut his teeth with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. ker tales were becoming generational staples as well. Rumors that Brian Jones was murdered spread rapidly. Most claimed that the construction crew working on Jones’ house killed the guitarist during an argument over money. Some said that the crew’s foreman accidently drowned Jones when a bit of drunken horseplay got too rough. A particularly juicy story claimed that Brian Jones was the victim of a satanic sacrifice.

ker tales were becoming generational staples as well. Rumors that Brian Jones was murdered spread rapidly. Most claimed that the construction crew working on Jones’ house killed the guitarist during an argument over money. Some said that the crew’s foreman accidently drowned Jones when a bit of drunken horseplay got too rough. A particularly juicy story claimed that Brian Jones was the victim of a satanic sacrifice. that Jones was full of wine and downers—a lethal combination on dry land, let alone in a heated pool.

that Jones was full of wine and downers—a lethal combination on dry land, let alone in a heated pool.