Throwing Stones XXII: The Prince Of Bankers

(This is Part XXII. Click here to read Throwing Stones Part XXI: Shattered)

In part XXI, the Stones struggled to deal with the fallout from the Altamont free concert.

As the sixties drew to close, Rupert Loewenstein noticed that some of the parties he and his wife attended were undergoing a strange transformation. Instead of enjoying drinks and conversation, an increasing number of guests were flopping on a couch or the floor and withdrawing into what appeared to be cosmic bliss or a brain-dead stupor.

As the sixties drew to close, Rupert Loewenstein noticed that some of the parties he and his wife attended were undergoing a strange transformation. Instead of enjoying drinks and conversation, an increasing number of guests were flopping on a couch or the floor and withdrawing into what appeared to be cosmic bliss or a brain-dead stupor.

On a few occasions, Loewenstein literally stumbled across such guests while saying his goodnights. One evening, he tripped over a skinny young man with long hair. Loewenstein apologized, and the young man seemed to take it all in stride. Months later, Loewenstein would realize that the young man was Mick Jagger, the famous face of The Rolling Stones.

Rupert Loewenstein could be forgiven for being behind the pop cultural curve. He was a well-respected merchant banker and a devoted classical music fan with zero interest in Top 40 trends. Though he made his home in Swinging London, sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll were about as far from his milieu as you could get.

Jagger may have been the crown prince of rock, but Rupert Loewenstein was an actual prince. Born in 1933, he was the sole progeny of the royal houses of Wittelsbach and Loewenstein-Wertheim. Loewenstein’s father was a German prince; his mother, a countess. Baby Rupert entered the world with a title, a coat of arms, twelve middle names and a family tree that winds its way through central European history like a trumpet vine wandering the walls of a crumbling castle. The only thing missing was an inheritance. Previous generations on both sides of the family had long since spent the money and sold off the ancestral estates.

Jagger may have been the crown prince of rock, but Rupert Loewenstein was an actual prince. Born in 1933, he was the sole progeny of the royal houses of Wittelsbach and Loewenstein-Wertheim. Loewenstein’s father was a German prince; his mother, a countess. Baby Rupert entered the world with a title, a coat of arms, twelve middle names and a family tree that winds its way through central European history like a trumpet vine wandering the walls of a crumbling castle. The only thing missing was an inheritance. Previous generations on both sides of the family had long since spent the money and sold off the ancestral estates.

Rupert Loewenstein’s father was surprised to learn that his new wife’s family fortune was gone, and she was burning through what was left with alarming speed. His mother was surprised to learn that her new husband wasn’t about to let marriage interfere with his pursuit of beautiful women.

Loewenstein’s parents were Catholic, but that didn’t stop the divorce. Disdain for Hitler and the fact that some of their ancestors were Jewish kept them out of Germany as the Nazis rose to power. Rupert was born in Majorca, Spain, and spent the war years in England with his mother. He attended private boarding schools and earned a scholarship to Oxford.

Loewenstein’s parents were Catholic, but that didn’t stop the divorce. Disdain for Hitler and the fact that some of their ancestors were Jewish kept them out of Germany as the Nazis rose to power. Rupert was born in Majorca, Spain, and spent the war years in England with his mother. He attended private boarding schools and earned a scholarship to Oxford.

Having watched his parents mismanage money for years, young Rupert developed a knack for common-sense financial decision making. After college, he accepted an entry-level position with the London offices of Bache & Co., a leading international securities and investment firm. The starting salary was low, but Loewenstein hoped to master skills that would make him a rich man someday. He married Josephine Lowry-Cory, a striking young British woman with a couple of barons and a lost fortune in her own family history. Though money was tight, the couple enjoyed entertaining, and the prince continued to add names to what would now be called his “golden Rolodex.”

Loewenstein worked hard at Bache, and became a skilled stockbroker, negotiator and financial advisor. Upper management decided that the gregarious, multilingual Loewenstein was the ideal man to open Bache’s string of new European brokerage offices. The prince proved them correct while enjoying a lifestyle well beyond his income, thanks to a generous expense account and a healthy travel and entertainment budget. The post-war Western economic boom was roaring toward its high watermark, and the prince and his clients rode the crest of the wave for all it was worth.

Loewenstein worked hard at Bache, and became a skilled stockbroker, negotiator and financial advisor. Upper management decided that the gregarious, multilingual Loewenstein was the ideal man to open Bache’s string of new European brokerage offices. The prince proved them correct while enjoying a lifestyle well beyond his income, thanks to a generous expense account and a healthy travel and entertainment budget. The post-war Western economic boom was roaring toward its high watermark, and the prince and his clients rode the crest of the wave for all it was worth.

In 1962, a wealthy client asked Loewenstein if he would be interested in going into commercial banking. Lowenstein put together a consortium of partners and investors that included his client and purchased Joseph Leopold & Sons, a London-based merchant bank, in 1963.

The bank proved stodgy, even by British standards. The new owners updated the antiquated bookkeeping system and expanded the business, but there was none of the recklessness seen in today’s financial sector. Lowenstein and his partners were largely playing with their own money, and acted accordingly. They dealt in corporate overseas investment, foreign letters of credit, currency trading and other business-oriented banking matters, all guaranteed to raise a yawn in casual conversation. They also offered personal and corporate financial management for select clients.

Five years after his team purchased the bank, Loewenstein got a call from a young art dealer and socialite named Christopher Gibbs. Gibbs had grown up wealthy, and his career choice kept him in contact with both new money and the old aristocracy. Gibbs had befriended Mick Jagger, and was surprised when Mick told him that The Rolling Stones were, for all practical purposes, broke. The band’s increasingly estranged American manager, Allen Klein, received all of their income, refused to share financial information, and sporadically sent them checks of varying sizes.

Five years after his team purchased the bank, Loewenstein got a call from a young art dealer and socialite named Christopher Gibbs. Gibbs had grown up wealthy, and his career choice kept him in contact with both new money and the old aristocracy. Gibbs had befriended Mick Jagger, and was surprised when Mick told him that The Rolling Stones were, for all practical purposes, broke. The band’s increasingly estranged American manager, Allen Klein, received all of their income, refused to share financial information, and sporadically sent them checks of varying sizes.

Jagger was desperate to find someone who could help his band regain financial control. He knew that Gibbs had friends in the financial world, and asked the art dealer to put him in touch with a qualified candidate willing to take on the job. It was no easy sell. London’s famously conservative bankers still wore bowler hats, and most wouldn’t have touched The Rolling Stones with a ten-foot umbrella. Gibbs had already been turned down by others when he called his princely pal.

Loewenstein was intrigued. He had begun feeling restless and, though he knew nothing about the Stones or their music, thought a rock group might make an interesting client. Christopher Gibbs told Lowenstein that Mick Jagger was far smarter and more personable than the Stones’ image let on. Loewenstein met with Jagger and confirmed Gibbs’ opinion.

Afterwards, Loewenstein realized that Jagger was the young man he had tripped over months before, but that didn’t stop him from agreeing to take on the band as a business client. The Rolling Stones’ bizarro showbiz fairytale had taken another improbable turn. Their prince had come.

Afterwards, Loewenstein realized that Jagger was the young man he had tripped over months before, but that didn’t stop him from agreeing to take on the band as a business client. The Rolling Stones’ bizarro showbiz fairytale had taken another improbable turn. Their prince had come.

(This concludes Part XXII. Look for Part XXIII, coming soon, only to Bill’s BrainWorks!)

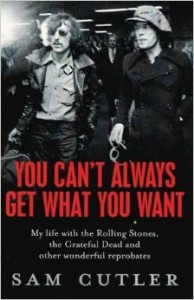

By the end of the sixties, Chip Monck had earned a hard-won reputation as one of the best stage, sound and lighting guys in the business. Having completed preparations for the free concert at the Sears Point Raceway, Monck suddenly had less than two days to tear everything down, truck it fifty miles east to the Altamont Speedway, and set it all up again. Like Tour Manager Sam Cutler, Chip Monck was a trooper. He rallied his largely volunteer crew and pulled off the final miracle of the improbable 1969 tour.

By the end of the sixties, Chip Monck had earned a hard-won reputation as one of the best stage, sound and lighting guys in the business. Having completed preparations for the free concert at the Sears Point Raceway, Monck suddenly had less than two days to tear everything down, truck it fifty miles east to the Altamont Speedway, and set it all up again. Like Tour Manager Sam Cutler, Chip Monck was a trooper. He rallied his largely volunteer crew and pulled off the final miracle of the improbable 1969 tour.

This suggestion seemed somewhat reasonable in 1969, especially if you were English. There were English Hells Angels, fifty of whom had helped out with The Rolling Stones successful free concert in Hyde Park. So when Scully pitched the American Angels in glowing, countercultural terms, describing the bikers as “righteous” and “dignified,” it sounded good to the Stones.

This suggestion seemed somewhat reasonable in 1969, especially if you were English. There were English Hells Angels, fifty of whom had helped out with The Rolling Stones successful free concert in Hyde Park. So when Scully pitched the American Angels in glowing, countercultural terms, describing the bikers as “righteous” and “dignified,” it sounded good to the Stones. During the rise of the San Francisco scene, a symbiotic relationship had evolved between musicians, event organizers and local Hells Angels chapters. When the bikers attended a show, they quickly staked out their turf, which fellow concertgoers nicknamed “Angel Land.” It was a land most non-Angels feared to tread. Organizers and promoters soon realized that by encouraging the strategic placement of Angel Land, they could create a buffer zone between the audience and potential problem areas like the soundboard, the power generators or the backstage entrance. The Angels were happy to occupy the suggested piece of real estate in exchange for cases of free beer.

During the rise of the San Francisco scene, a symbiotic relationship had evolved between musicians, event organizers and local Hells Angels chapters. When the bikers attended a show, they quickly staked out their turf, which fellow concertgoers nicknamed “Angel Land.” It was a land most non-Angels feared to tread. Organizers and promoters soon realized that by encouraging the strategic placement of Angel Land, they could create a buffer zone between the audience and potential problem areas like the soundboard, the power generators or the backstage entrance. The Angels were happy to occupy the suggested piece of real estate in exchange for cases of free beer.