Throwing Stones XV: For A Song

(This is Part XV. Click Throwing Stones XIV:Bad Apples to read the previous chapter.)

In Part XIV, Rolling Stones’ Manager Allen Klein made his play for The Beatles as the Stones worked on a new album.

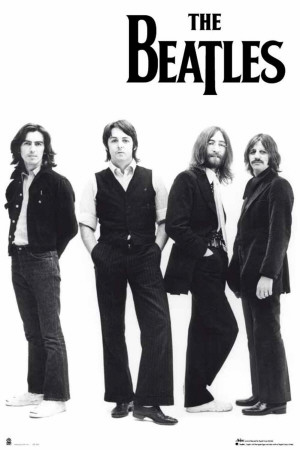

By February, 1969, John Lennon was convinced that Allen Klein was the ultimate rock ’n’ roll manager. Mick Jagger was no longer sure. Four years after The Rolling Stones signed with Klein, Jagger and the rest of the band had grown deeply distrustful of the blustery American.

Initially, Klein had been generous with the Stones, doling out large sums of money with a smile. In 1966, when Keith Richards inquired if he could afford to buy a home in one of London’s toniest neighborhoods, Klein cut the guitarist a check for the full purchase price. But as time went by, the checkbook tightened, and Mick Jagger in particular began to suspect that their wily manager was getting the best of the Stones’ business deals.

Initially, Klein had been generous with the Stones, doling out large sums of money with a smile. In 1966, when Keith Richards inquired if he could afford to buy a home in one of London’s toniest neighborhoods, Klein cut the guitarist a check for the full purchase price. But as time went by, the checkbook tightened, and Mick Jagger in particular began to suspect that their wily manager was getting the best of the Stones’ business deals.

Klein had an ironclad contract, and didn’t appreciate being questioned or second-guessed. Getting either money or answers out of him became increasingly difficult. Eager to warn John Lennon of Klein’s behavior, Mick Jagger set up a meeting with his fellow rocker. But when Jagger arrived, he was stunned to see that Lennon had invited Allen Klein as well. Wary of a direct confrontation with Klein, Jagger left with his famous lips sealed.

Perhaps he should have met with Lennon’s songwriting partner instead.

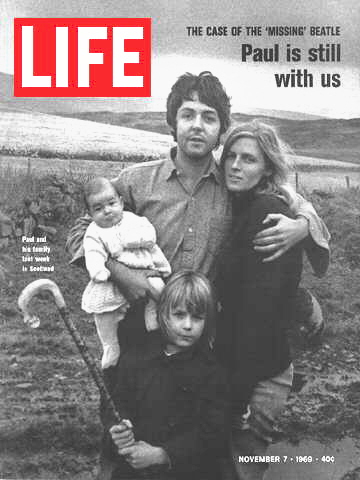

After splitting with actress Jane Asher, Paul McCartney had fallen in love with Linda Eastman, a young American photographer. Contrary to still-popular rumors, Linda Eastman was not the heir to the Eastman-Kodak fortune. But she was from a wealthy New York family. Linda’s father, Lee Eastman, was one of the world’s top intellectual property lawyers, and had decades of entertainment industry experience. Linda’s brother, John, had recently joined her father’s practice.

After splitting with actress Jane Asher, Paul McCartney had fallen in love with Linda Eastman, a young American photographer. Contrary to still-popular rumors, Linda Eastman was not the heir to the Eastman-Kodak fortune. But she was from a wealthy New York family. Linda’s father, Lee Eastman, was one of the world’s top intellectual property lawyers, and had decades of entertainment industry experience. Linda’s brother, John, had recently joined her father’s practice.

Before Allen Klein met John Lennon, Paul McCartney had suggested that Lee and John Eastman were ideal candidates to sort out the mess at Apple Corps. Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr had initially agreed. They had no viable alternatives to suggest, and were duly impressed by the Eastmans’ expertise. Still, they were understandably concerned that Linda’s family members would be biased towards Paul, especially after he married Linda on March 12, 1969. What’s more, they had grown to resent what they saw as McCartney’s pushiness regarding the band’s business and creative efforts. Eventually, the idea of the Eastmans and Allen Klein co-managing the band was suggested as a reasonable compromise.

Though John Lennon had abdicated his role as the leader of The Beatles for years, he had grown to resent McCartney the most of all. Paul had made a tremendous effort to accommodate Yoko Ono, but Ono had her own agenda, and stoked Lennon’s ire. In retrospect, it’s no surprise that John Lennon took an immediate (although unjustified) dislike to the Eastmans, decrying them as pretentious, social climbing, elitist snobs. Klein was more than happy to join Lennon in parroting this line to Harrison and Starr.

In a meeting at Apple attended by both Klein and the Eastmans, Klein, Lennon and Ono mercilessly baited Lee Eastman, goading the lawyer into exploding at Klein. Lennon then claimed that Eastman’s outburst proved Paul’s New York attorney in-laws were nothing more than pompous, self-important phonies.

When the four Beatles sat down to decide who would manage the band and handle the turnaround at Apple, Allen Klein got three votes. The Eastmans got one. The Fab Four had a standing rule that all significant decisions had to be unanimous, and McCartney was shocked to hear his bandmates insist that the rule was no longer valid—Klein had won by majority and that was that. It was the beginning of the end.

When the four Beatles sat down to decide who would manage the band and handle the turnaround at Apple, Allen Klein got three votes. The Eastmans got one. The Fab Four had a standing rule that all significant decisions had to be unanimous, and McCartney was shocked to hear his bandmates insist that the rule was no longer valid—Klein had won by majority and that was that. It was the beginning of the end.

Allen Klein moved into Apple and began slashing staff. But Klein’s cuts were motivated by more than simple cost savings. He wanted absolute control. Thus, good, loyal, hardworking employees were thrown out with the bad apples. That included Ron Kass, the seasoned record executive who had made the company’s record division its one shining success. Talent scout and producer Peter Asher (Jane’s brother) had also played a vital role in Apple Records’ achievements. Asher refused to let Klein humiliate him, and resigned before he could be fired. He went on to become one of the most successful producers of the rock era.

Klein renegotiated The Beatles’ contract with EMI, substantially increasing their royalty rate. He also brought Apple’s expenses under control. But his aggressiveness cost the Beatles their chance to buy back the Estate of Brian Epstein’s financial interest in the band. Epstein’s spooked heirs sold it to an investment trust instead, blindsiding The Beatles.

Meanwhile, music publisher Dick James had grown weary of John and Yoko’s increasingly odd public behavior and wary of the band’s ongoing business imbroglios. James held a controlling interest in Northern Songs, Ltd., the publicly held publishing company that owned the Lennon-McCartney team’s song copyrights. John and Paul were minority shareholders; George and Ringo owned small stakes as well.

James announced that he was selling his interest to ATV Entertainment, a conglomerate owned by Lord Lew Grade, a cigar-chomping British showbiz mogul. The Beatles felt utterly betrayed. Klein promised to stop the sale. But neither Klein nor the Eastmans were able to prevent it, especially after a frustrated John Lennon foolishly threw a tantrum in a critical meeting and denounced a group of potential white knight co-investors as just another bunch of greedy businessmen.

James announced that he was selling his interest to ATV Entertainment, a conglomerate owned by Lord Lew Grade, a cigar-chomping British showbiz mogul. The Beatles felt utterly betrayed. Klein promised to stop the sale. But neither Klein nor the Eastmans were able to prevent it, especially after a frustrated John Lennon foolishly threw a tantrum in a critical meeting and denounced a group of potential white knight co-investors as just another bunch of greedy businessmen.

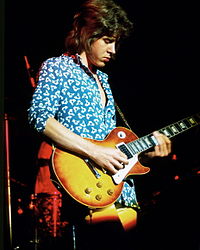

But what of The Rolling Stones? Unlike their Liverpool pals, Jagger and Richards’ outfit was firing on all cylinders. The addition of guitarist Mick Taylor had turbocharged their most creative period. Their rollicking summer single, “Honky Tonk Women,” spent weeks at number one on both the U.S. and U.K. charts. The band’s first U.S. tour in over three years was penciled in for the fall, along with another appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. A new album was scheduled for release as soon as the tour wrapped. The Stones had even decided to title the LP “Let It Bleed,” in sly mockery of their rivals’ (as yet unreleased) “Let It Be.”

But what of The Rolling Stones? Unlike their Liverpool pals, Jagger and Richards’ outfit was firing on all cylinders. The addition of guitarist Mick Taylor had turbocharged their most creative period. Their rollicking summer single, “Honky Tonk Women,” spent weeks at number one on both the U.S. and U.K. charts. The band’s first U.S. tour in over three years was penciled in for the fall, along with another appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. A new album was scheduled for release as soon as the tour wrapped. The Stones had even decided to title the LP “Let It Bleed,” in sly mockery of their rivals’ (as yet unreleased) “Let It Be.”

With the Fab Four falling apart, every Stones concert would serve as a coronation. Jagger and Richards were confident that the band would return from America crowned as the reigning kings of rock ’n’ roll. And then, they discovered that there was no money available to fund a tour.

(This concludes Part XIV. Click now to read Throwing Stones XVI: Highway ’69 Revisited!)

Bryan T.

Lots of fascinating information, and really fun to read. It’s an unhappy factor that so much great, generation-spanning music came from a foundation flooded with so many ill feelings. Upon Klein’s death, which I think occurred in the cushy settings of a trans-continental flight, Todd Rundgren was heard to say, “Too easy for him.”

Dan O.

So now you’re Charles Dickens, eh, Bill–ending your installments with a cliffhanger? As a parallel account of the Stones and the Beatles, this was a particularly interesting chapter. The writing just keeps getting stronger. Well done!

George B.

Ironically, I read this on the same day I read a piece on the 50th anniversary of the Fab Four’s first trip to the US and their first Ed Sullivan Show. Watching Sullivan clips on the CBS Morning News brought it all back in a flash. As I’ve said in past comments, a few notes from a song can whip one back in time and re-establish a particular state of mind in nano seconds. So can your pieces. I agree with Dan… well done!

Jim B.

Great stuff, Bill. Saw Sir Paul and Ringo on the Grammy show recently. Can’t believe they, like the Stones, are still at it after all these years. Hope for us all. Keep it coming. We’re all waiting to know how–and if–the story ends.

Jonell M.

Bill, I always look forward to your pithy and interesting “e-magazine” {I know it’s called a blog, but that doesn’t seem like the proper word given the agility of your wit and the skill you have in bringing the information together} and I pass it on regularly. Thank you for keeping worthy conversations going.

Larry McC.

Have you ever heard any of Linda Eastman’s vocal tracks that are isolated from the rest of Wing’s vocals? She was truly awful. They just buried her tracks in the mix, and used auto-tune and other studio tricks like they did with Cher and some of the legendary off-pitch singers. Should have stuck to taking pictures.

Ro

In my experience, everyone in the music business made money except the talent. Until the talent started writing their own songs, then realized that what was written is the contracts mattered just as much. That fine print! I remember John & Yoko being “artistic” with their nude photos, politics and general aloofness. Zzzzz… I put on my earbuds this morning and the Stones kicked in when I hit the trail–kicking up stones behind me.

Shully

Thanks for continuing the bizarre, behind-the-guitars history of the Rolling Stones–exploring the seldom-revealed back roads, side stories and business blunders in Mick and Keith’s biographies. It’s an almost-unbelievable tale of monumental success, extraordinary excess and colossal financial naiveté. Together, your chapters form a serialized satirical masterpiece showcasing the weirdness that has shadowed them throughout their career. Over their more than 50 years as a rock group, the Stones have lost, squandered, mismanaged or been swindled out of more money than all other successful bands combined (with the possible exception of The Beatles). Looking forward to learning how they turned it around and wound up richer than ever.