Throwing Stones II: If You Sign Me Up

(To Read Part I, click Throwing Stones.)

Part I covered the excessive ticket prices for the Rolling Stones’ 50th Anniversary Tour, then time-tripped to 1960’s London to trace the roots of the band’s branding.

Sixteen months before Andrew Oldham began managing the Stones, the Beatles were the kings of the Liverpool scene and little more. Britain’s entertainment industry was based in London, and record companies had next to no interest in an act from a Northern city that, as Keith Richards would later say, “might as well have been Nome, Alaska.”

Bu t Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein was nothing if not persistent, and as 1961 entered the history books, he had exciting New Year’s news for his unsigned band: They had a shot at a contract with Decca records. Decca would ultimately pass on the Beatles with the soon-to-be-infamous line, “Guitar groups are on their way out.” A year later, the Beatles were a chart-storming sensation, and Decca Records was the laughingstock of the industry.

t Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein was nothing if not persistent, and as 1961 entered the history books, he had exciting New Year’s news for his unsigned band: They had a shot at a contract with Decca records. Decca would ultimately pass on the Beatles with the soon-to-be-infamous line, “Guitar groups are on their way out.” A year later, the Beatles were a chart-storming sensation, and Decca Records was the laughingstock of the industry.

The rap Decca took for turning down the Beatles was hardly fair. In truth, every major British record company had passed on the band. Decca simply had the misfortune of being the last to do so, and of doing so with such a memorably inaccurate turn of phrase. The Beatles eventually signed with Parlophone, the runt of the litter of labels owned by corporate big dog EMI. All of EMI’s other labels had already rejected them.

Lucky for Decca, George Harrison didn’t hold a grudge. While appearing on the TV show “Jukebox Jury,” Harrison told fellow guest-judge and Decca A&R Director Dick Rowe about a great new band. A rockin’ R&B outfit called The Rollin’ Stones. Having blown his shot at the Beatles, Rowe wasn’t about to ignore Harrison’s hot tip.

Lucky for Decca, George Harrison didn’t hold a grudge. While appearing on the TV show “Jukebox Jury,” Harrison told fellow guest-judge and Decca A&R Director Dick Rowe about a great new band. A rockin’ R&B outfit called The Rollin’ Stones. Having blown his shot at the Beatles, Rowe wasn’t about to ignore Harrison’s hot tip.

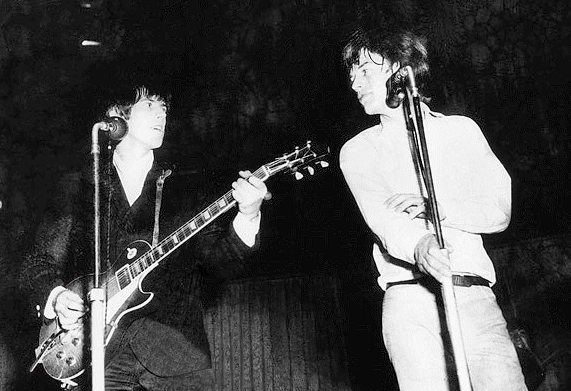

The Rollin’ Stones had officially appointed Andrew Loog Oldham as their manager on May 1, 1963. Oldham took the band shopping for new threads on Carnaby Street a few days later. Good timing. The next night, Dick Rowe caught the Stones at London’s Crawdaddy Club. They were even better than he had hoped.

Tired of being lampooned as a tin-eared boob in the teenybopper mags and the mainstream press, Dick Rowe was ready to do whatever it took to sign the Rollin’ Stones. Advantage: Andrew Loog Oldham.

Still too young to legally sign contracts himself, Oldham had formed a partnership with Eric Easton, an old school music biz manager who appeared to be (gasp!) “nearly forty.” While the flamboyant, controlling, egotistical Oldham wasn’t happy about having a partner, he and Easton seemed like a good team in the beginning.

Oldham knew rock and pop. He had press contacts, a vision for the band and a tremendous sense of style. More importantly, he had his finger on the pulse of an emerging market, and was one of the few people to realize that the music business was in the early stages of a revolution. Easton had industry experience, a no-nonsense attitude and the relationships required to shove a band up the showbiz ladder. More importantly, he had the cash to back Oldham.

Easton and Oldham negotiated a phenomenal recording contract for the Stones. The band got creative control, an impressive royalty rate, and the opportunity to eventually own their recorded masters. Decca got the band. It was an unprecedented deal for a new act.

Oldham added a “g” to the Stones first name, subtracted an “s” from Keith Richards’ last name, and booted beloved pianist Ian Stewart out of the band. Oldham believed the talented ivory-tickler lacked the requisite pop-star good looks, and besides, six was one too many members for young fans to adore. Why Bill Wyman’s hair wasn’t fired remains a mystery. The bassist is still the only performer to serve more than 25 years in a major rock band without a single good hair day.

Though he knew next to nothing about recording, Oldham dreamed of becoming England’s answer to Phil Spector. He declared himself the band’s producer and forged ahead. The Rolling Stones’ first single, a remake of Chuck Berry’s “Come On,” made it to the middle of the British Top 40. It was a respectable showing, but the follow-up had Oldham flummoxed.

made it to the middle of the British Top 40. It was a respectable showing, but the follow-up had Oldham flummoxed.

Record execs expected teen-oriented acts to fade quickly. Their strategy was simple: milk a hit-maker for as much product as possible before fickle young fans moved on to the next big thing. Bands were required to churn out a new single every three months and two LPs a year, plus EPs and promotional product. Grueling tour schedules, radio and TV commitments, and the constant demand for new material combined to create a distinctly Darwinian dynamic. Only the strongest bands would survive.

The Stones’ repertoire of blues, soul and rock ’n’ roll covers worked well in the clubs, but was unlikely to supply a steady stream of hit singles. When the recording date for the second single arrived, Andrew Loog Oldham found himself in the studio with a hot band and no song. It appeared that the Rolling Stones’ career and Andrew Oldham’s dream were both dead on arrival.

(This concludes Part II. For Part III, click Throwing Stones III: Write Yer Own.)

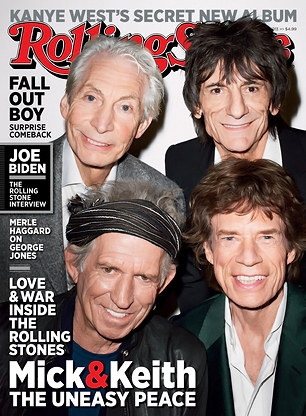

Before you accuse me of being jaded, get a gander at the May 23rd issue of Rolling Stone magazine, which, to absolutely no one’s surprise, features the band on the cover. Again. Meanwhile, the article inside sheepishly reports that a ticket for the gang’s latest go ’round starts, that’s right, starts, at $150 and spirals upward to somewhere north of $2000. With prices like these, who needs scalpers?

Before you accuse me of being jaded, get a gander at the May 23rd issue of Rolling Stone magazine, which, to absolutely no one’s surprise, features the band on the cover. Again. Meanwhile, the article inside sheepishly reports that a ticket for the gang’s latest go ’round starts, that’s right, starts, at $150 and spirals upward to somewhere north of $2000. With prices like these, who needs scalpers? Like it or not, we live in an era in which the terms “band” and “brand” have become interchangeable. An era in which the Rolling Stones will continue to be awarded iconic status. Ironic might be more suitable. Because, contrary to the fundamental tenants of marketing, the longer the Stones continue as a band, the more they damage their brand.

Like it or not, we live in an era in which the terms “band” and “brand” have become interchangeable. An era in which the Rolling Stones will continue to be awarded iconic status. Ironic might be more suitable. Because, contrary to the fundamental tenants of marketing, the longer the Stones continue as a band, the more they damage their brand. By positioning the Rolling Stones as the anti-Beatles and relentlessly flogging their rebellious image, Oldham defined the Stone’s public perception for decades. The Stones, for their part, were more than happy to play along. They fancied themselves an authentic Chicago blues band—the kind of willful denial of reality that only teenagers in their first rock group or someone with a serious head injury can muster—and dreaded being sold as suit-wearing sunshine boys. Besides, just as being sly, witty and charming came naturally to the Beatles, being snotty, scrappy and scruffy came naturally to the Rolling Stones. Going with Oldham’s flow was an assignment they could handle.

By positioning the Rolling Stones as the anti-Beatles and relentlessly flogging their rebellious image, Oldham defined the Stone’s public perception for decades. The Stones, for their part, were more than happy to play along. They fancied themselves an authentic Chicago blues band—the kind of willful denial of reality that only teenagers in their first rock group or someone with a serious head injury can muster—and dreaded being sold as suit-wearing sunshine boys. Besides, just as being sly, witty and charming came naturally to the Beatles, being snotty, scrappy and scruffy came naturally to the Rolling Stones. Going with Oldham’s flow was an assignment they could handle.

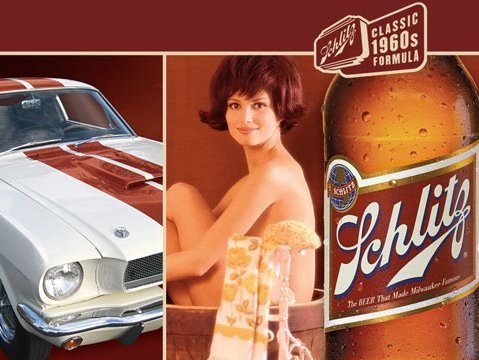

names or street addresses. As “Classic 60’s Formula” Schlitz struggles, Yuengling has become the cool American lager of the moment, siphoning off the buzz that Schlitz had hoped to call its own.

names or street addresses. As “Classic 60’s Formula” Schlitz struggles, Yuengling has become the cool American lager of the moment, siphoning off the buzz that Schlitz had hoped to call its own.

Meanwhile, my calls to Schlitz have gone unreturned. Still, if I can find a bottle of their new-old formula, I’ll gladly give it a go. The folks who brew Schlitz have tried to do the right thing, and for that alone, the brand deserves a shot. Who knows? Decades after it disappeared, now may be the time to give Gusto another chance.

Meanwhile, my calls to Schlitz have gone unreturned. Still, if I can find a bottle of their new-old formula, I’ll gladly give it a go. The folks who brew Schlitz have tried to do the right thing, and for that alone, the brand deserves a shot. Who knows? Decades after it disappeared, now may be the time to give Gusto another chance. Fast forward to 2007. Pabst Brewing had been sold several times, eventually morphing into a holding company that owned several beer brands, including Pabst Blue Ribbon, Schlitz, Stroh’s, Old Milwaukee and more. The company contracts out the production of these beers, operating no breweries of its own.

Fast forward to 2007. Pabst Brewing had been sold several times, eventually morphing into a holding company that owned several beer brands, including Pabst Blue Ribbon, Schlitz, Stroh’s, Old Milwaukee and more. The company contracts out the production of these beers, operating no breweries of its own.

Other things had changed as well. Wine had gone mainstream. Hard liquor was back, inspiring expensive, super-premium products and a cocktail craze. And all of the famous American breweries founded by German immigrants in the 1800s had been swallowed by conglomerates.

Other things had changed as well. Wine had gone mainstream. Hard liquor was back, inspiring expensive, super-premium products and a cocktail craze. And all of the famous American breweries founded by German immigrants in the 1800s had been swallowed by conglomerates. into his fridge and stealing his last six-pack. Thunderstruck viewers felt like the town bully had gone on a bender and busted into their living rooms in a beer-fueled rage. The nerve! After all, they hadn’t messed with this psycho’s Schlitz; Schlitz had messed with his Schlitz!

into his fridge and stealing his last six-pack. Thunderstruck viewers felt like the town bully had gone on a bender and busted into their living rooms in a beer-fueled rage. The nerve! After all, they hadn’t messed with this psycho’s Schlitz; Schlitz had messed with his Schlitz! Unlike Schlitz, PBR had not been reformulated. But its image had. As Schlitz self-destructed, Blue Ribbon’s decline took a steep turn for the worse. The brand never recovered. Tellingly, the “popular price” beer category eventually came to be known as the “sub-premium” category.

Unlike Schlitz, PBR had not been reformulated. But its image had. As Schlitz self-destructed, Blue Ribbon’s decline took a steep turn for the worse. The brand never recovered. Tellingly, the “popular price” beer category eventually came to be known as the “sub-premium” category. Blue Ribbon’s dive and Schlitz’s suicide had Miller looking like a sure thing. Certain that Anheuser-Busch’s golden boy was on the ropes, Phillip Morris execs moved in for the win. They didn’t realize the easy part was over.

Blue Ribbon’s dive and Schlitz’s suicide had Miller looking like a sure thing. Certain that Anheuser-Busch’s golden boy was on the ropes, Phillip Morris execs moved in for the win. They didn’t realize the easy part was over. The baby boomers lack of enthusiasm for hard liquor was a boon to America’s beer makers. But while both the Joseph Schlitz and Anheuser-Busch brewing companies were hugely successful, neither was outrageously profitable. Brewing is an expensive process that requires a unique combination of high quality ingredients and time. Shortchanging either is risky business.

The baby boomers lack of enthusiasm for hard liquor was a boon to America’s beer makers. But while both the Joseph Schlitz and Anheuser-Busch brewing companies were hugely successful, neither was outrageously profitable. Brewing is an expensive process that requires a unique combination of high quality ingredients and time. Shortchanging either is risky business. re-orgs.

re-orgs. For three-quarters of the twentieth century, two great brands stood toe-to-toe and slugged it out for the heavyweight title of America’s most popular beer. Then, to the astonishment of its loyal fans, one took off the gloves and pounded itself into oblivion in a few short rounds.

For three-quarters of the twentieth century, two great brands stood toe-to-toe and slugged it out for the heavyweight title of America’s most popular beer. Then, to the astonishment of its loyal fans, one took off the gloves and pounded itself into oblivion in a few short rounds. A wide-ranging array of restaurants offered a taste of their wares, including old favorites like Sunset Grill, Tin Angel and Merchants, more recent arrivals like Table 3 and The Pharmacy, and corporate big guns like Aquarium and Rainforest Café. The list is far too long to mention all of them here, though not quite long enough to have kept me from stuffing myself with samples from nearly every station.

A wide-ranging array of restaurants offered a taste of their wares, including old favorites like Sunset Grill, Tin Angel and Merchants, more recent arrivals like Table 3 and The Pharmacy, and corporate big guns like Aquarium and Rainforest Café. The list is far too long to mention all of them here, though not quite long enough to have kept me from stuffing myself with samples from nearly every station. My hopes that Sue would have a sister along were answered by “Hap & Harry’s® Lynchburg Lager.” This isa refreshing entry with a slight sweetness and a crisp finish, brewed by Yazoo in partnership with Tennessee distributor R.S. Lipman. It’s a beer that every Yuengling lover could love, and one whose local charm could easily end a romance with the pride of Pennsylvania.

My hopes that Sue would have a sister along were answered by “Hap & Harry’s® Lynchburg Lager.” This isa refreshing entry with a slight sweetness and a crisp finish, brewed by Yazoo in partnership with Tennessee distributor R.S. Lipman. It’s a beer that every Yuengling lover could love, and one whose local charm could easily end a romance with the pride of Pennsylvania. A forgotten American favorite, rye whiskey is distinguished by a mash bill in which rye, rather than corn, is the dominant grain. Typically viewed as bourbon’s bolder, spicier cousin, rye whiskey began making a comeback in the early 2000s. Today, stores that once struggled to scrounge up a bottle of Old Overholt® offer an ever-growing list of ryes in a range of prices. Though announced last fall, George Dickel Rye has just started showing up on many stores’ shelves. It’s a welcome addition, combining the spice and citrus notes one expects in a rye with a sweet smoothness that makes for easy sippin’, even at 90 proof.

A forgotten American favorite, rye whiskey is distinguished by a mash bill in which rye, rather than corn, is the dominant grain. Typically viewed as bourbon’s bolder, spicier cousin, rye whiskey began making a comeback in the early 2000s. Today, stores that once struggled to scrounge up a bottle of Old Overholt® offer an ever-growing list of ryes in a range of prices. Though announced last fall, George Dickel Rye has just started showing up on many stores’ shelves. It’s a welcome addition, combining the spice and citrus notes one expects in a rye with a sweet smoothness that makes for easy sippin’, even at 90 proof. Collier and McKeel® Tennessee Whiskey, meanwhile, was being made just a few miles from where westood. A taste quickly revealed that Collier and McKeel is no Dickel or Daniel’s knockoff. Though corn dominates its mash bill, a helping of rye gives this small batch upstart a spicier taste than other Tennessee Whiskies, while charcoal filtering keeps things smooth. If you like American whiskies, but have a hard time deciding between bourbon, rye and Tennessee whiskey, Collier and McKeel may be the ideal resolution to your dilemma.

Collier and McKeel® Tennessee Whiskey, meanwhile, was being made just a few miles from where westood. A taste quickly revealed that Collier and McKeel is no Dickel or Daniel’s knockoff. Though corn dominates its mash bill, a helping of rye gives this small batch upstart a spicier taste than other Tennessee Whiskies, while charcoal filtering keeps things smooth. If you like American whiskies, but have a hard time deciding between bourbon, rye and Tennessee whiskey, Collier and McKeel may be the ideal resolution to your dilemma.

So, nearly 210 years after Pennsylvania farmers realized that fighting an overwhelming force would be a fatal error, Maker’s Mark called the whole thing off. Fresh from their weeklong digital tarring and feathering, Bill Samuels and his son, President and CEO Ron Samuels, announced that they had heard their customers loud and clear. They made a mistake, and they were sorry. Maker’s Mark would continue to be bottled at 90 proof. “You spoke. We listened,” Maker’s tweeted, including a link to a full apology on Facebook.

So, nearly 210 years after Pennsylvania farmers realized that fighting an overwhelming force would be a fatal error, Maker’s Mark called the whole thing off. Fresh from their weeklong digital tarring and feathering, Bill Samuels and his son, President and CEO Ron Samuels, announced that they had heard their customers loud and clear. They made a mistake, and they were sorry. Maker’s Mark would continue to be bottled at 90 proof. “You spoke. We listened,” Maker’s tweeted, including a link to a full apology on Facebook.

You probably heard about the Whiskey Rebellion in high school. You may even confuse it with the Fake ID Citation or the Raid On Dad’s Beer Fridge. To clarify, the Whiskey Rebellion was the first true test of the power of the federal government. In an effort to pay off debts accumulated during the revolutionary war, newly minted Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton pushed a tax on whiskey producers through congress. An angry public pushed back, particularly in Pennsylvania.

You probably heard about the Whiskey Rebellion in high school. You may even confuse it with the Fake ID Citation or the Raid On Dad’s Beer Fridge. To clarify, the Whiskey Rebellion was the first true test of the power of the federal government. In an effort to pay off debts accumulated during the revolutionary war, newly minted Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton pushed a tax on whiskey producers through congress. An angry public pushed back, particularly in Pennsylvania. As often happens when large amounts of booze are involved, things got ugly fast. In 1791, “whiskey rebels” tarred and feathered a tax inspector and a process server. By 1794, shots were being exchanged, a rebel leader was killed, a tax inspector’s home was torched and armed mobs were threatening Pittsburgh.

As often happens when large amounts of booze are involved, things got ugly fast. In 1791, “whiskey rebels” tarred and feathered a tax inspector and a process server. By 1794, shots were being exchanged, a rebel leader was killed, a tax inspector’s home was torched and armed mobs were threatening Pittsburgh.